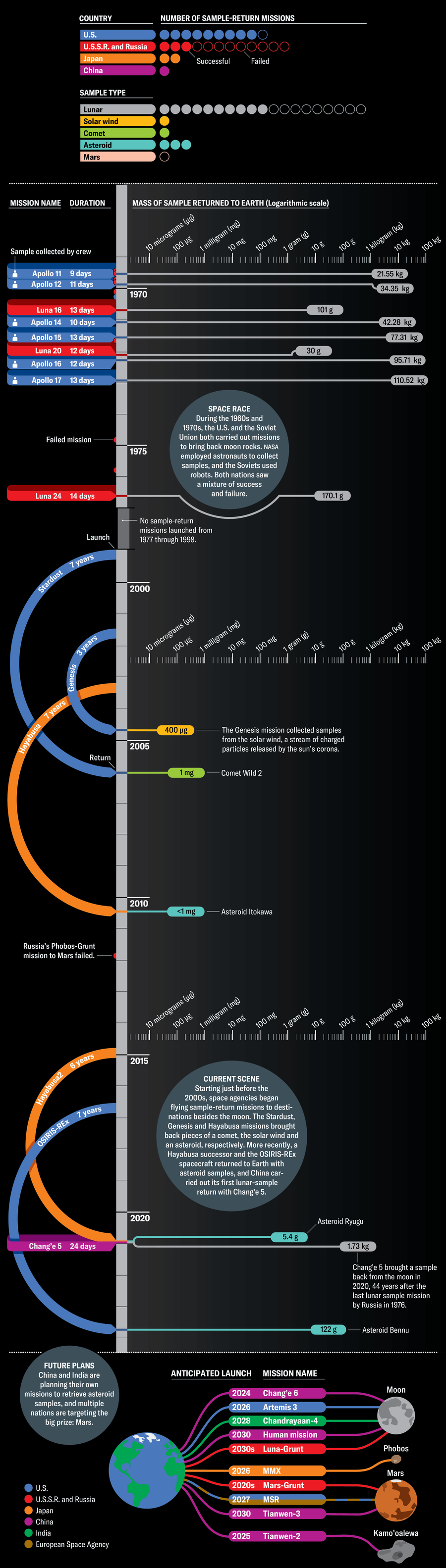

Visiting moons, asteroids and planets is great, but taking a piece of them home is even better, according to traditional space wisdom. Bringing samples to Earth allows scientists to study them with the full breadth of existing laboratory technology, whereas only limited analyses are possible on other worlds. Yet retrieving samples from such locations requires not just getting there but launching off the surface and getting home, too. “It’s hard to do, and as a result, it hasn’t been done very often,” says space historian Roger Launius.

Although humans have sent 10 successful landers to Mars, no one has yet brought bits of Mars to Earth. That could change in the coming decade, though, as NASA and space agencies in Europe, China, Russia and Japan have proposals in the works to achieve this milestone. NASA's Perseverance rover has already collected samples on the Red Planet in preparation for a future retrieval mission.

Credit: John Knight

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.