Tamara had not been sleeping well. Some days she woke up at four o’clock in the morning in tears and overwhelmed by a feeling of helplessness. She had moved her family three times over the past six years. Her house in New Hampshire was shot at—possibly by someone aiming at the rainbow signs in her front yard. In 2022 she fled to Massachusetts, which seemed to be safer for her child, Grey, who is transgender. But whenever she hears the words “safe state,” a thought pops into her head: “Austria felt like a safe place in World War II, too.”

For the time being, Grey feels like they are in a good place mentally. (For their personal safety, the names of young people and their parents in this story have been changed.) They have found a community that sees them for who they are and a state that allows them to receive the gender-affirming care they need. But they have seen dark times before, and the familiar drumbeat of anxiety never quite goes away. “I am always a little concerned in the back of my head that things are getting kind of bad in some places, and maybe that’ll happen to me,” Grey says.

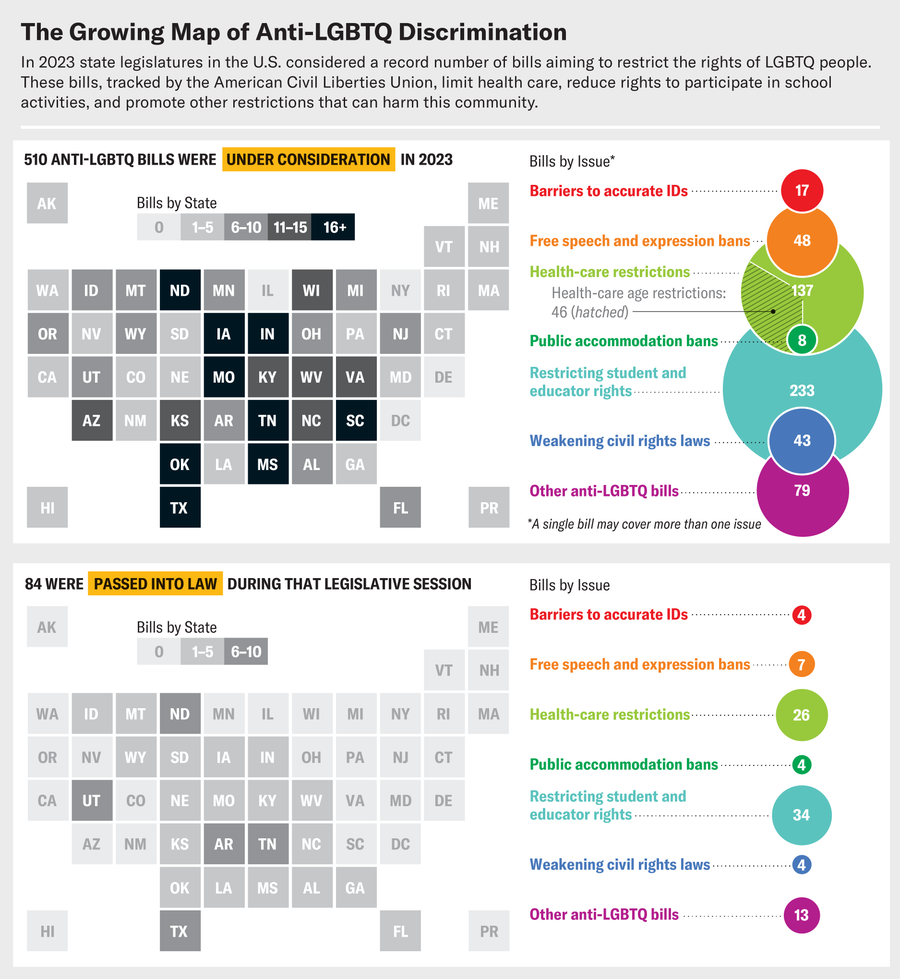

For many families with LGBTQ kids, the dark times are now. More than 500 anti-LGBTQ bills were considered in state legislatures in 2023, and 84 passed. (The term “LGBTQ” refers to lesbian, gay, and other people with minority sexual orientations and gender identities.) These bills restrict discussions of LGBTQ people or history in schools, limit legal protections for queer and transgender youth, and prohibit transgender health care for minors and even adults.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The sheer volume of these bills, and the sentiment behind them, is doing harm. An estimated 71 percent of LGBTQ youths—including 86 percent of transgender and nonbinary kids—say that laws concerning LGBTQ people have had a negative impact on their mental health. Nearly half of LGBTQ kids seriously considered suicide in the previous year, according to a survey conducted in 2022 by the Trevor Project, a nonprofit group that offers crisis services.

Discrimination against LGBTQ kids is also taking a toll on parents’ mental health, and the added family stress can make things even worse for their children. Studies show that family support is critical to the psychological resilience of queer and trans kids. But many parents are filled with fear, grief and anxiety, and the strain makes it harder for them to shield their children from the harshness of an often hostile world. “No one can be empathic with your fists clenched,” says Lisa Diamond, a psychologist at the University of Utah. “I’ve come to believe that we cannot help LGBTQ youth without taking stock of the amount of vigilance and worry that is eating up the nervous systems of their parents. You can’t heal one without the other, because if that kid really matters to you, there is no way that their fear can’t make you afraid.”

In reporting this story, I spoke with 20 parents, and some of their kids, in North Carolina, Georgia, Texas, Florida, Ohio, California, New York and Massachusetts. Our conversations revealed just how widespread their fears are. Tamara, Grey’s mom, tried for months to stop anti-LGBTQ bills when she lived in New Hampshire. She and others were spit at and called “groomers” and “pedophiles” after speaking at a legislative session. Then there were the bullets grazing her house.

Still, families are finding ways to cope. A grassroots movement is creating safe spaces for parents, such as online communities that enable parents and caregivers to support one another and networks to help them find LGBTQ-friendly places to raise their kids. They are crafting positive narratives, focused on their families, filled with strength and growth and hope. Those narratives are helping them make meaning from their hardship while envisioning a future where their loved ones are no longer under attack.

Francis came out to their family as pansexual and nonbinary in 10th grade, with a group text. The text explained that they would prefer to be called by a new name and referred to with they/them pronouns, and although they didn’t expect their conservative Catholic family to understand, they hoped their relatives would respect their wishes.

“I was terrified,” Francis recalls. They had been seeing a therapist for years, but the counselor wasn’t well versed in LGBTQ issues. “I knew I needed to come out so that I could get further support, whether that be from another therapist or somebody in my family at least recognizing my pronouns and my name,” Francis says.

The first texts Francis got back from family members were positive: “we love you for who you are.” But within a few months they learned that their parents had quite different feelings. Their dad ignored the issue, staying silent rather than using Francis’s new name and pronouns. Their mom, Lois, kept questioning what it meant for them to be nonbinary or trans. She knew people who were trans, “but when it is your own kid,” she says, “it seems so different.”

Given the large number of young people who identify as LGBTQ—about 25 percent of high school students are not heterosexual, according to a 2021 survey—remarkably little research has focused on the experiences of their parents, says David Huebner, a clinical psychologist at the George Washington University. The queer community has compensated for lost family ties with the narrative of a “chosen family”: even if your parents reject you, you can depend on other LGBTQ people, who become like siblings. That sentiment might work for adults, but it doesn’t ring true for minors who rely on their families for even the most basic needs.

In 2009 Huebner and Caitlin Ryan, director of the Family Acceptance Project at San Francisco State University, published one of the first studies showing that parents’ attitudes matter a lot. The research found that lesbian, gay or bisexual teens who were rejected by their parents or caregivers were eight times more likely to attempt suicide than those who were accepted.

But parents’ reactions don’t necessarily fit into the simplistic binary of rejecting or accepting. “It’s a journey, a very bumpy journey,” says Roberto Abreu, a psychologist at the University of Florida. Abreu and others have shown that parents can experience a gamut of emotions after their kid comes out as queer or trans—shock, confusion, sadness, worry, guilt, fear, grief, anger—and it can take two years or more for those emotions to abate. They often feel overwhelmed by the disconnect between their earlier beliefs about their child’s identity and what that child is telling them now. The burden of navigating schools, health care, and other systems to support their child adds to the strain.

“There’s just a lot of stress and anxiety around the unknown; like, what am I supposed to do?” Lois says. She and her husband held wildly different views on gender and how to care for Francis, which caused a fracture in their marriage. “It’s like walking on glass. It’s really scary,” she says.

Some parents grieve the loss of the child they thought they had and their visions for that child’s future. These expectations are often tied to outdated conceptions of gender and sexual orientation that are being challenged as more people come out as LGBTQ and expand our understanding of human experience. For example, gender is not necessarily fixed at birth. A study in JAMA Network Open found that most transgender children sense a mismatch between their biological sex and their gender identity by age seven. Sarah, the mother of a six-year-old transgender girl in New York State, still feels a pang whenever she comes across something adorned with her daughter’s male birth name, which many trans people call a deadname. She and her husband named each of their children after a relative who had passed away to keep the memory of their deceased loved ones alive.

“That’s a complicated thing for parents, I think, because how can you feel grief over something that clearly your kid is experiencing joy over—being their true selves?” Sarah says. Sarah recalls reading somewhere that grief is just love with no place to go, and those words resonated with her.

Unresolved grieving for a person who is still present yet different is an experience that psychologists sometimes refer to as ambiguous loss. In families of LGBTQ children, such loss may affect not just the parents but also their kids. Work led by Jenifer McGuire, a professor of family social science at the University of Minnesota, suggests transgender children can experience ambiguous loss when their family responds to their identity in conflicting ways. Family members might remain physically present but become psychologically absent, ignoring the gender transition and prompting a sense of loss in the children.

Grey, who is nonbinary, gets support from their father and mother. The family has had to move several times because they felt unsafe.

Credit: Gioncarlo Valentine

For Francis, there was a certain amount of sadness when their expectations of what life would be like after coming out brushed up against reality. They transferred to a new high school, where they met some like-minded friends. Their mom got them into a gender clinic in Ohio, where they were referred to a psychologist who helped them address their distress at the mismatch between their gender identity and their sex assigned at birth. Psychiatrists, after thorough consultation, recommended they start their medical transition with hormone treatments. But during one appointment, Francis’s dad said he thought what they were doing was wrong and insisted they forgo treatment.

“It was really earth-shattering,” Francis says. “I had been very sad about a lot of things, about not being accepted by everybody. But when he had completely shut it down, I was very, very angry. We’ve gone through the other possibilities, we’ve gone through the other options, and all the doctors are telling you that this is what needs to happen.”

Every major medical association in the U.S., including the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Medical Association and the Endocrine Society, endorses gender-affirming care for trans kids. Such care ranges from counseling to social affirmation to medical interventions such as hormone therapy. Numerous research studies have linked this form of care to better mental health. For example, one study looked at nearly 22,000 trans people nationwide who sought hormone therapy. It found that those who started receiving hormones as teens had fewer suicidal thoughts and a lower rate of substance abuse than those who were forced to wait until adulthood.

Still, Francis was afraid to argue with their dad. Lois, their mom, promised she would never let their dad kick them out of the family home, but Francis wasn’t so sure. “The scared part of me was [thinking]: Don’t say too much. Because I still need a place to live. I still need a safe space.”

Lois was angry and scared, too, and worried that Francis would lose hope. She reminded them that they would turn 18 in a little more than a year and suggested they make a calendar to count down the days.

Francis put the date into their phone, but seeing the time tick by in an interminable number of hours and minutes only fueled their anxiety. So they bought several packs of colorful Post-It notes, numbered each for the hundreds of days they had left until the birthday that would give them independence and pasted them all over one wall of their bedroom. “It was a bizarre thing to do,” Francis says. But the notes kept them going.

Compared with other kids their age, LGBTQ youths are at higher risk of numerous mental health issues, including depression, anxiety, substance abuse, self-harm and suicide. These health issues have been largely ascribed to minority stress, the consequences of social sources of tension that come with a marginalized identity. These stressors are not an innate part of an LGBTQ identity. Rather they emerge from experiencing repeated prejudice and powerlessness.

Now some researchers believe that the minority stress theory should be expanded to include parents of queer and trans kids, who experience a loss of privilege and normalcy and contend with oppressive institutions on behalf of their family. In a small study of 40 parents of transgender children, parents reported experiencing rejection from their extended family, as relatives refused to learn about their children’s transition or criticized their parenting. They feared being mistreated by friends, other parents and their community for not enforcing societal norms surrounding gender identity.

For many families, the moment a kid comes out of the closet, the parents get into the closet, unsure of how to deal with a secret that is not their own. When Cristina, a mother in North Carolina, first learned that her oldest kid was bisexual, she worried about how the members of her conservative church would react. “There was a lot of fear. I didn’t want people to know; I didn’t know how to frame it,” she recalls. “I was just terrified that I was going to be cast out of my circles and not supported if I supported my kid. So I went underground with that info.”

This type of anticipated rejection or stigma is a key driver of minority stress. Coming out is often considered a lifelong process because people who are queer or trans must constantly negotiate how openly they want to exist in society, deciding whether they should share that aspect of their identity or keep it to themselves. “One of the things that is associated with negative mental health outcomes for LGBTQ people is concealment. And concealment is basically the flip side of outness,” says Josh Goodman, a psychologist at Southern Oregon University. “The same thing goes for parents, too.”

Simon, a gay teen, recalls how as a child he would hide his dolls whenever guests visited. Although he expected his parents to be supportive, he says it was still hard to tell them he was gay, “like pulling a knife out of your throat.” When he was in the seventh grade, he was at a neighborhood convenience store when a man called him a “disgusting f****t.” Simon put down the drink he was about to buy and walked straight home. Every time he goes back to that store, which he does often, he feels a little sick to his stomach. “That moment is instilled in my mind.”

Credit: Jen Christiansen; Source: American Civil Liberties Union (data)

His mom didn’t learn about the episode until weeks later, and when she did, she was filled with guilt that she somehow had allowed it to happen. She decided to send Simon to a more progressive, accepting high school one county away. She started daring herself to tell people he was gay, as if educating those around him were a talisman against future harm. And she tried to follow his lead whenever possible. “If he’s going to be fearless, I need to be fearless,” she says.

Fear is a major source of stress for many parents of LGBTQ kids. They worry their kids will be lonely, suffer from poor mental health, and experience violence or victimization. And those worries cause parents to react in ways they are not always proud of. One mother told me she cried when her daughter came out to her as bisexual: “I just knew that her life was going to be so much more difficult.”

This notion that being gay means pain and suffering reinforces stigma, yet it has some basis in reality. According to a 2023 study by the Trevor Project, 24 percent of LGBTQ youths reported that they were physically threatened or harmed in the past year because of either their sexual orientation or their gender identity; those who were threatened or harmed also reported attempting suicide at nearly triple the rate of those who were not.

Jacqueline, a mother of two in Florida, was roused from her sleep one September morning as the telephone persistently rang several rooms away. The mother of a friend of one of her children, Adrian, was on the line. She wanted to know if the youngster was okay. Adrian had texted suicide notes to that friend and others in the middle of the night. Jacqueline rushed out of her room and found Adrian lying on the floor, convulsing. On the ambulance ride to the hospital, her mind was a jumble of worry and dread.

“Is Adrian going to be okay? Is there going to be brain damage? I didn’t know,” Jacqueline recalls. “I was in shock. I thought, I can’t believe this is happening; I just cannot believe this is happening.”

Adrian had come out as trans to their parents the year before, when they were 14. Adrian’s father, who came from a conservative background, consistently misgendered them. The boys at their school were all bigger and appeared more masculine, and they felt like their gender was constantly being questioned. Eventually it got to be too much, and Adrian sent those texts.

Five years later and after many hours spent under the care of medical professionals, Adrian is doing well. They’re a junior in college, living in an apartment with their older brother 15 minutes away from their parents. Their father finally accepted their identity. Jacqueline texts them every day, and if they sound “off,” she rushes over to see them. “I always worry,” she says. “I’m still scared that something might happen.”

Diamond, the University of Utah psychologist, says this hypervigilant state can be devastating to parents. She has studied minority stress in members of the LGBTQ community and in their caregivers, and she believes the absence of safety erodes their mental health. The same response designed to protect humans from the proverbial saber-toothed tiger is now perpetually activated by headlines signaling that LGBTQ kids are threatened.

“We humans need to feel a sense of belonging—it’s our birthright as a social species,” Diamond says. “When we feel that there’s something about us or our family that’s off, then we just go into that evolutionary state of watch out.” Diamond’s work suggests that being in that constant state of uncertainty could be as detrimental to a person’s overall well-being as experiencing a traumatic event. Her research indicates that all this worry can cause some parents to become more controlling and authoritarian, driven by the desire to protect their kids from danger or judgment.

For example, parents might keep their kids from LGBTQ-centric events such as Pride parades or discourage them from publicly disclosing their pronouns. Even if the intention is to protect, these tactics can create a vicious cycle. One recent study linked higher levels of parental psychological control—that is, trying to coerce kids into thinking or behaving differently—with more depressive symptoms among LGBTQ youth.

Looking back, Tamara regrets how she insisted on constantly cutting Grey’s hair and nails, nervous about what would happen if they didn’t adhere to the gender norms of the rural Texas town where they first lived. Although Grey recalls being bitter about it at the time, they can see now why their mom thought their identity had to be kept under wraps. “You don’t necessarily want to be the weird feminine one mixed in with that group of people,” Grey says. “She wasn’t really making a bad decision in my mind. It’s hard to figure out what to do because both decisions are kind of hurtful, just in different ways.”

In helping their kids embrace their authentic selves while trying to keep them out of harm’s way, parents of LGBTQ youth are walking a tightrope between freedom and safety. That act is getting even trickier as anti-LGBTQ legislation sweeps the nation. “I think the burden of these bans, and stigma and discrimination more broadly, on the population is even bigger than we estimate,” says Kerith Conron, research director at the Williams Institute, based at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Law. “It’s not just the individual; it’s these broader ecological ripple effects.”

Researchers working to understand the child-parent dynamic have been harassed by some of the same groups trying to make the lives of LGBTQ people and their families so miserable. Last year Abreu, the psychologist at the University of Florida, partnered with Russ Toomey, a developmental scientist at the University of Arizona, and the Human Rights Campaign (HRC) Foundation to conduct the first large-scale, national study of parents and caregivers of trans and nonbinary children. The study gathered parents’ perspectives in a variety of contexts, asking about their mental health and their child’s gender identity development, the barriers they faced and the support systems that helped them. The researchers shared the survey through the HRC Foundation and online groups where parents of trans youth congregate. More than 1,400 parents responded.

But anti-trans groups got ahold of the survey and sent hostile e-mails to Abreu and Toomey. One group penned letters to their universities’ presidents and institutional review boards, as well as boards of regents, governors and heads of the departments of education in both states, claiming the research was unethical and was harming youth. “That’s the first time I’ve ever had an outside entity file a grievance against the ethics of research that I have engaged in in nearly 20 years,” Toomey says. “That professional attack is quite jarring to take.”

Toomey is working on publishing the study results. He hopes the research will inform policies to better support and educate the parents of trans youth.

Unlike parents of children in many other minority groups, most of those raising queer and trans kids don’t have lived experiences to inform them and are often unsure how to support their LGBTQ offspring. So they are turning to peer-support groups. PFLAG, formerly known as Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, runs such groups, and many parents have found a sense of purpose and belonging that has helped them strengthen relationships with their children. But some parents aren’t comfortable talking about these issues in a group setting. Others live in communities without a local chapter; according to some estimates, only about 10 to 15 percent of parents of LGBTQ children ever make it to a PFLAG meeting.

Instead many parents gather virtually, seeking crowd-sourced advice from Reddit or joining one of countless Facebook groups. Every day these platforms are filled with posts from parents searching for information and a sense of community. They are looking for recommendations on affirming churches and therapists; asking for guidance on sex talks and same-sex sleepovers; talking through experiences with school bullies, haircuts and hormone therapies. These online communities can help parents navigate this journey, giving them a place to open up to other parents who have been in their position before and can show them what’s ahead. More experienced parents can correct commonly held misconceptions and connect newcomers to resources that can help them better understand and support their kid.

One such online community, called Mama Bears, started in 2014 with 150 members, most of them conservative Christians. Cristina, the mom in North Carolina, was one of them. She says the group supported her as she reexamined her faith, a process that was often frightening and messy. “[We were] holding each other up but at the same time challenging each other to continue moving forward,” she says, “to start learning about what acceptance of your kid really means.”

Today Mama Bears is more wide-ranging, with more than 39,000 members and various programs serving the greater LGBTQ community. Liz Dyer, the group’s founder, says she has seen a complete shift in the conversations parents are having, moving from topics such as religious acceptance to concerns about protecting their children. “Mothers are very worried. But what we have found is that knowledge and education really empower parents. And once they feel more empowered and capable and knowledgeable, a lot of their anxiety—I don’t want to say it dissipates, but it’s easier for them to cope with.”

In addition to the communities parents are building for themselves, some LGBTQ-focused organizations are expanding their services to help families. In Austin, Tex., a small nonprofit called Out Youth has created several programs for parents, including “family office hours” that offer hour-long counseling sessions for caregivers and family members. It also started caregiver-support groups, which provide a six-week crash course on parenting a trans, nonbinary or questioning child. And Out Youth piloted a caregiver peer-support program, which paired more experienced parents of trans kids with those whose kids had just come out.

“The thing that I’ve learned, and that I’ve said from the beginning of doing this work, is that caregivers and their young person are on separate yet intersecting journeys,” says Sarah Kapostasy, who formerly served as Out Youth’s clinical director. “Sometimes caregivers need a separate space.” If parents have a place where they can figure things out away from their family, it can keep their kids from being burdened by negative feelings those parents are going through and from taking on such feelings about themselves.

Eventually many parents experience a kind of positive transformation as they adjust to their child’s identity, research suggests, and they often end up redefining their own identity as the parent of an LGBTQ kid. Dani Rosenkrantz, a psychologist and researcher in Florida, says that although parenting a trans kid is often cast as a hard role filled with grief and pain, she has heard a more positive narrative emerge lately about parents witnessing their worldviews expand and their children flourish.

“I have learned so much from my child, and I just feel very proud of who she is and how she’s had the courage to speak that truth,” Sarah, the mother in New York, told me. “We owe it to our kids to make a more informed, enlightened world for them.” One study by researchers at the University of Kentucky set out to catalog the positive aspects of parenting an LGBTQ child. The survey of 142 parents uncovered various ways the experience brought about parents’ personal growth. It made them more compassionate, gave them greater empathy for marginalized populations, strengthened their relationship with their children, connected them more fully to their values, led to lasting friendships, and motivated them to engage in activism and advocacy.

But trying to make the world a better place for their own kids and the rest of the LGBTQ community can expose families to hatred and danger. One parent in Georgia told me that after she organized the first Pride celebration in her town, she received warrants for her arrest listing a dozen city and state violations, among them “enticing a child for indecent purposes.” (The charges, which were traced back to a right-wing activist organization, were dismissed by a judge before being brought to trial.)

Adrian, a transgender youth, shares a hug with their mother.

Credit: Gioncarlo Valentine

Another parent, a single father to a 12-year-old trans boy in Florida, says he can no longer protest anti-LGBTQ bills, because it raises risks of repercussions for his child. “You always balance out your ideals, your principles, your goals as a citizen with the needs of your family,” he says. He has developed an exit plan in case his home state becomes even more hostile. He has passports ready and is prepared to quit his teaching job and start his own company, moving to another state or abroad if necessary. Being able to think about leaving, a privilege he recognizes many parents do not have, has bolstered his mental health.

To help families of trans kids move to safer places, volunteers have created relocation networks. There are GoFundMe pages to help cover moving costs, and allies post information in a variety of locations to connect parents to good school districts, friendly neighborhoods and affirming-health-care providers. Parents can consult various color-coded maps to see which states are safest, such as the LGBTQ Equality Maps drafted by the Movement Advancement Project, a nonpartisan think tank.

Mama Bears has created a relocation-assistance program to contribute to the effort, but Dyer says she hopes parents use it only as a last resort. “It is not going to help the movement to set trans people free if everybody that is affirming abandons red states.”

Tamara has heard that concern several times since moving her family to Massachusetts. But she doesn’t regret her decision, which she knows was best for Grey and for her and her husband, too. “For us, our mental health is aligned with our kid’s mental health,” she says.

Yet even now, in an apparently safer place, she and her husband still find themselves trying to protect Grey from the news, transphobic relatives and hostile people on the street. Recently the three of them went for a walk through their city. Tamara noticed that they had fallen into “bodyguard mode”: one parent in the front, one parent in the back and their only child in between.

Marla Broadfoot reported this story while participating in the Rosalynn Carter Fellowship for Mental Health Journalism.

If You Need Help

If you or someone you know is struggling or having thoughts of suicide, help is available. Call the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988, use the online Lifeline Chat, or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741741.