The year was 2011. Barack Obama was president, NASA’s space shuttles were retiring and Taylor Swift was on her second tour—and across a huge swath of the southeastern U.S., billions of tiny newborn cicadas rained down from tree branches to burrow into the soil.

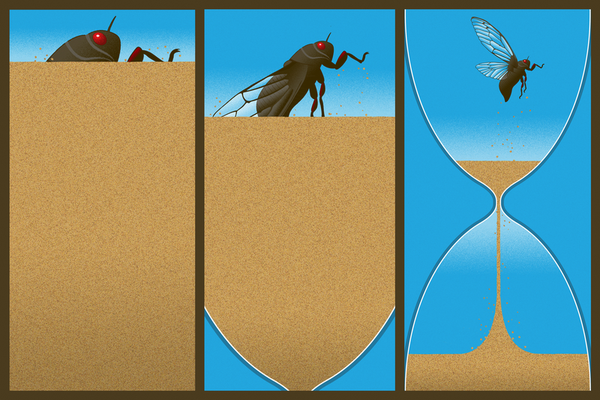

This spring those cicadas, now grown, will venture aboveground for the first time in 13 years. It’s a marvel of synchronization that allows the insects to thrive despite the vast range of animals that feast on the tasty, defenseless bugs. But how do periodical cicadas like these manage to coordinate their emergence every 13—or, for some species, 17—years? After all, cicadas aren’t equipped with an alarm clock or a calendar, and they spend more than a decade underground.

“Seventeen [years] is just an inordinately long time to keep track of anything,” says John Lill, an insect ecologist at George Washington University. “I can’t keep track of five years, let alone 17, myself—so how an insect does it is pretty remarkable.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In 2024 two different periodical cicada groups will emerge: the 13-year Brood XIX, which will blanket much of the southeastern U.S., and the 17-year Brood XIII, which will be concentrated in northern Illinois. There will also be some stragglers from other broods. Cicadas most commonly mistime their emergence by either one or four years—and next year another massive cohort of 17-year cicadas, Brood XIV, is due across parts of the East Coast and Ohio River Basin.

But none of these insects, whether on time or early, are marking the passage of time. Instead periodical cicadas have a hack: they tally the growing cycles of the trees that they feed on.

During their long stint underground, the insects sip at xylem sap, the nutrient-poor but water-rich liquid that moves from the tips of a tree’s roots up to its canopy. Each year as a tree buds and blossoms, its xylem is briefly richer in amino acids, leading one team of researchers to call it “spring elixir.” Cicadas appear to count each flush of spring elixir: when those scientists took 15-year-old cicadas from a 17-year brood and manipulated the trees that the insects were feeding on so that they grew leaves twice in one year, voilà—the cicadas emerged a year early, having tallied the required 17 leaf-outs.

“We know that’s what they count; where they’re putting their little chalk marks on the wall, we don’t know,” says Martha Weiss, an insect ecologist at Georgetown University. “We don’t really understand how they’re keeping track of it.”

The seven species of periodical cicadas in the U.S. are particularly flashy because of their synchronized emergences, but the nation is home to about 150 cicada species, all told. Nonperiodical cicadas in the U.S. are dubbed “annual cicadas” because some of these insects emerge every year. But scientists don’t yet know exactly how long these insects live or whether they carry an internal counter like the 13- and 17-year cicadas clearly do, says John Cooley, a biologist at the University of Connecticut whose research focuses on cicadas. “They’re out every summer, so they’re hard to track, and underground it’s all kind of a mess,” he says of annual cicadas.

Cooley says that at least in the periodical cicadas, however, discovering the counter would be an intellectually trivial—albeit a very financially costly—endeavor. Researchers could just analyze enough cicadas at stages from hatchling to adult and look for a pattern in the insects’ internal states, he says.

More challenging than finding the mysterious counter is understanding how the mechanism and the bizarre lifestyle it enables evolved in the first place, Cooley says. One hypothesis connects the periodic lifestyle to the glaciers that once blanketed much of cicadas’ current territory; other scientists point to the way the tactic helps the bugs escape their predators.

But although neither a glacial history nor a bevy of predators are rare, periodical cicadas certainly are—just nine of the about 3,400 cicada species known worldwide synchronize periodical emergences—so something else is going on, Cooley argues. “Whatever the circumstances are that lead to the evolution of this life-history pattern, they are rare, and the rare things are always the hardest things to study,” he says. “We can’t tell you why this evolved; we just know it has to be some special collection of circumstances.”

So this spring and summer, if you live in or can get to the eastern U.S., try to revel in the mysteriousness of periodical cicadas, no matter how loud they get. “[The periodical cicadas’ emergence] really is one of the seven biological wonders of the world. There is nowhere else in the entire world where you can see so many periodical cicada species,” Cooley says. “It’s something that really nobody else in the world gets the privilege of seeing.”