Between 1969 and 1972, Apollo astronauts brought back to Earth a total of nine containers of moon material that were sealed on the lunar surface.

Two of the larger sealed samples were collected by Apollo 17 moonwalkers in December 1972. Three sealed samples from Apollo 15, 16 and 17 remain unopened.

According to several key lunar researchers, now is the right time to consider opening at least one of the still-sealed sample containers. [NASA's 17 Apollo Moon Missions in Pictures]

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Protected, preserved and processed

Home for the Apollo geological samples—specimens that are physically protected, environmentally preserved and scientifically processed—is the Lunar Sample Laboratory Facility, a special building at NASA 's Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston.

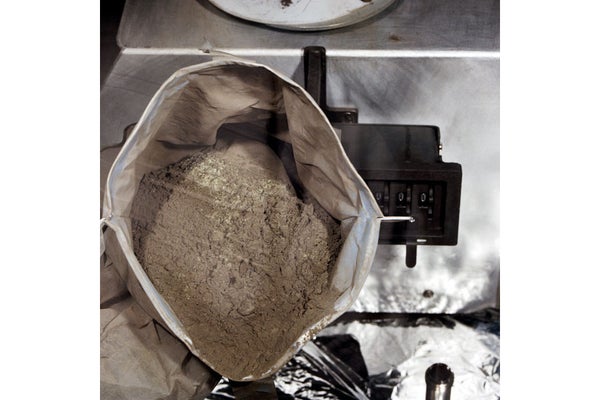

The Apollo collection consists of lunar rocks, core samples, pebbles, sand and dust from the lunar surface. Thanks to the six Apollo landing expeditions, 2,200 separate samples made it back to Earth, snagged from six different exploration sites on the moon.

Returned lunar samples have shown that they are the gifts that keep on giving. For instance, water from the moon's interior was detected recently by sensitive mass spectrometric analysis of basaltic glasses brought back to Earth by the Apollo 15 and Apollo 17 missions.

Careful planning

"Samples were intentionally saved for a time when technology and instrumentation had advanced to the point that we could maximize the scientific return on these unique samples," said NASA's Ryan Zeigler, Apollo sample curator and manager of the Astromaterials Acquisition and Curation Office in Houston.

But such investigations require careful planning and execution by a consortium of experts with experience in handling and analyzing lunar samples, Zeigler told Space.com.

"Given the recent renewed interest in the moon, and specifically about the volatile budget of lunar regolith, these sealed samples likely contain information that would be important in the design of future lunar missions," Zeigler said.

"Volatiles" are substances with relatively low boiling points—materials such as water, hydrogen and methane. Understanding lunar volatiles could improve the productivity and value of future human involvement with the moon, scientists have stressed.

New insights

Zeigler isn't the only researcher who'd like to unseal some of the remaining Apollo samples. He's joined in this advocacy by Charles Shearer of the Institute of Meteoritics, Department of Earth and Planetary Science at the University of New Mexico and Clive Neal at the Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering & Earth Sciences at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

They'll be making their case later this month at the 49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, which is organized by the Lunar & Planetary Institute in Houston, an arm of the Universities Space Research Association. The conference will be held in The Woodlands, Texas, from March 19 through March 23.

"Given the new emphasis on the lunar volatile story, having these unopened samples will, apart from yielding new lunar science insights, allow us to plan the sampling, return and analysis of volatile-bearing lunar samples," Neal told Space.com. "Hence a consortium approach in analyzing these and similar samples is the only way to go."

Pristine and unstudied

Apollo's set of unopened samples contain pristine and unstudied lunar material. Moreover, given that the total sample mass within the unopened containers of moon specimens exceeds projected masses returned by future robotic missions, each of the unopened samples should be treated as an individual lunar mission, the lunar experts contend.

For example, the researchers point to "unopened treasures" in the Apollo 17 sample collection.

The Apollo 17 mission in December 1972 was a "J-style" mission. That means it was capable of a longer stay time on the moon and greater surface mobility via a wheeled vehicle. The expeditionary crew of Harrison "Jack" Schmitt and Eugene Cernan chalked up a total distance of 23 miles (36.9 kilometers).

Thanks to their moon rover, the lunar twosome gathered samples over a wide area in Taurus-Littrow Valley. The Apollo 17 mission returned 244 lbs. (110.5 kilograms) of a variety of sample types. This was approximately 30 percent of the total sample mass returned by the Apollo program, which collectively added up to 840 lbs. (381 kg). [Apollo 17: NASA's Last Apollo Moon Landing Mission in Pictures]

Seal status

But there's a bit of a catch.

The unopened containers appear to be sealed based on their outward appearance. However, it's doubtful that the containers still retain the level of vacuum that exists on the moon. It is expected that the containers retain a more modest vacuum and that the samples have not come in contact with the terrestrial atmosphere.

The bottom line is, nobody knows for sure the status of the seals until the containers are opened.

On one hand, the containers used during the Apollo program were a reasonable attempt to preserve many characteristics of the lunar regolith. But more important, these types of sample-containment concepts not only are expected to be used during future human missions to the moon, but may be applicable to robotic missions to the moon and other planetary bodies.

Zeigler and his associates suggest it would be prudent to assume that analytical techniques will continue to improve in the future and science goals will change with additional observations and data.

"Therefore, we are advocating opening a single sample container and saving the remaining two samples for future generations of lunar scientists," Shearer, Neal and Zeigler wrote in a paper they plan to present at the upcoming conference.

On a personal note

A lot of serious thought over the past decade has gone into why and how to study the unopened lunar samples, said Carlton Allen, former astromaterials curator at JSC. He, too, is a supporter of opening one of the Apollo sample collections now, giving the following reasons:

Technology: Techniques are available to examine sealed samples before opening and to open them with minimal terrestrial contamination.

Microanalysis: We can analyze trace gases and volatiles with the precision and accuracy needed to address fundamental questions in lunar science, such as the trace water in pyroclastic glass returned from the moon.

Lunar science: We understand many of the remaining gaps in lunar knowledge prior to a new era of exploration, and the precision/accuracy needed to address these gaps, such as existence and history of near-surface water and ice at a range of locations and temperatures.

Finally, Allen said there's a personal note, too.

"Some of the astronauts who collected these samples, technicians who opened and documented core tubes and scientists who studied samples all the way back to Apollo are still with us and professionally active," Allen said. "We should not overlook these irreplaceable human resources."

EDITOR'S RECOMMENDATIONS

Copyright 2017 LiveScience.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.