The latest phase of China’s bid to become a dominant space power is underway as the nation’s new robotic mission hurtles toward an orbit overlooking the far side of the moon. The relay satellite Queqiao, or “Magpie Bridge”—a reference to Chinese folklore—departed Earth atop a Long March 4C booster on Monday local time (Sunday evening in North America) from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center. The outbound trip will take a little over a week, although Queqiao will only reach its final orbit two months from now.

The mission will act as a vital link in China’s burgeoning network of robotic spacecraft around and on the moon while also performing novel scientific experiments that could lead to new discoveries in cosmology, astrophysics and astrobiology.

Queqiao will be positioned 40,000 miles (roughly 60,000 kilometers) above the moon’s far side in an orbit that lets it relay signals between Earth and China’s Chang’e 4 farside lander/rover, expected to be lofted in December. Together with Queqiao, two microsatellites—Longjiang 1 and 2, developed by China’s Harbin Institute of Technology—hitched a ride for release into lunar orbit to investigate radio bursts from the sun.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

From the Lunar Far Side to Cosmic Dawn

One of the premier scientific instruments onboard the farside relay spacecraft is the Netherlands–China Low-Frequency Explorer (NCLE), built by a team of Dutch scientists and engineers.

Mounted on the satellite’s chassis, NCLE is the first Dutch-made scientific instrument to be sent on a Chinese space mission, and is the result of a 2016 agreement between the Netherlands Space Office and the China National Space Administration. When the satellite settles into its final orbit months from now, it will wait for Chang’e 4’s arrival at the moon in early 2019. Then NCLE’s three five-meter-long antennas will be rolled out and the scientific work will start.

Built to carry out cutting-edge radio science and astronomy, the radio antennas’ top duty is to precisely measure radio waves originating from the period immediately after the big bang—the so-called “dark age” of the cosmos, when the universe was bereft of stars. Through its studies NCLE could help pinpoint when the dark age ended in a “cosmic dawn,” as the first stars began to shine. “NCLE is a stepping-stone towards a larger radio array in space,” says project leader Albert-Jan Boonstra, an astronomer at ASTRON Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy. That array could be “either a radio interferometer on the farside surface of the moon or a slowly drifting constellation of many small satellites.”

A Moon Garden

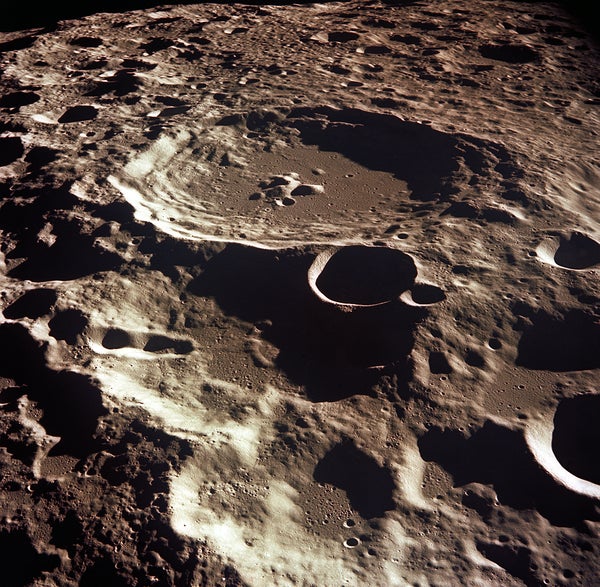

All this is a prelude to China’s Chang’e 4 lander/rover mission, expected to be sent moonward by a Long March 3B booster this December. A candidate landing region for Chang’e 4 is the southern floor of Von Kármán, a 180-kilometer-wide crater within the South Pole–Aitken impact basin—the largest of its kind on the moon.

Chang’e 4 will carry a cluster of international payloads from Germany, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia and Sweden. The lander will also tote a “lunar mini biosphere” experiment, designed by 28 Chinese educational institutions led by Chongqing University. Weighing roughly seven pounds, this experiment will attempt to germinate seeds from potatoes and Arabidopsis, a small flowering plant related to cabbage and mustard. It may additionally include a number of silkworm eggs. The biosphere package also contains water, air and nutrients, which will hopefully allow the seeds and eggs to briefly flourish in their protective capsule on the lunar surface. A tiny camera and data transmission system will allow researchers to see when and if the seeds blossom.

Little Steps, Big Goals

China’s cislunar (the area of space between Earth and its moon) exploration program is designed to be conducted in three phases: The first is simply reaching lunar orbit, a task completed by Chang’e 1 in 2007. The second is landing and roving on the moon, as Chang’e 3 did in 2013. The third is snagging lunar samples and rocketing them back to Earth—a challenging objective meant to be incrementally advanced by Chang’e 4 and two follow-up missions, Chang’e 5 and 6. “China’s launch of the Queqiao relay satellite ushers in a new era of lunar infrastructure that will enable full exploration of the moon, including the poorly known lunar far side,” says James Head, a planetary scientist at Brown University. “Similar to the way in which GPS and communications satellites on the Earth provide an infrastructure for our activities in orbit and on the ground here,” he adds, “the Queqiao relay satellite underlines the robustness of China’s comprehensive plans for lunar exploration, including the upcoming Chang'e 4 farside lander and rover, the Chang'e 5 nearside sample-return mission, and lunar polar exploration beyond.”

Paul Spudis, a planetary scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute, views China’s robotic missions as “part of a long-term, sustained effort to establish Chinese cislunar presence.” He suggests the Chinese relay satellite, after first serving its assigned tasks, might later be useful for more speculative and visionary missions.

“In the case of Chang’e 4, after its main mission is complete I would move the relay satellite to a high ‘storage’ orbit and have it become part of a future comsat network,” Spudis says.