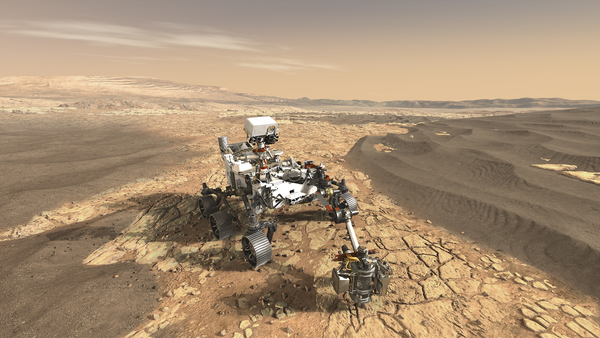

Earthlings have big plans for Mars. Next year NASA will launch Mars 2020—its most ambitious rover yet—to prepare for a future effort to robotically return samples of Martian rock to Earth to seek signs of past or present life. The agency also plans to send astronauts to Mars sometime in the 2030s, and new heavy-lift rockets being developed by SpaceX could conceivably land humans on the Red Planet even sooner. Meanwhile the meteoric rise of small, low-cost interplanetary CubeSats—the first of which flew by Mars late last year—suggests large numbers of more modest missions to Mars could soon be in the offing.

But all these plans hinge on whether Earth’s emissaries, human or robotic, can visit Mars and elsewhere without causing irreparable harm via “forward contamination” (introducing Earthly microbes to other worlds) or “back contamination” (importing putative alien pathogens to Earth). Hammered out over decades of international debate, the safeguards against both scenarios are collectively known as planetary protection. And, according to a NASA report released last week, they are in dire need of updating.

“The landscape for planetary protection is moving very fast. It’s exciting now that for the first time, many different players are able to contemplate missions of both commercial and scientific interest to bodies in our solar system,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, in a recent statement. “We want to be prepared in this new environment with thoughtful and practical policies that enable scientific discoveries and preserve the integrity of our planet and the places we’re visiting.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Generated in three months under the auspices of a newly formed 12-member Planetary Protection Independent Review Board (PPIRB)—chaired by Alan Stern, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute—the report presented nearly 80 findings and suggestions for guiding future missions. Chief among them was the recommendation that the PPIRB reconvene every few years to update its assessments in light of new scientific discoveries and technological developments. Although some stakeholders argue such efforts would boost public and private missions by allowing NASA to adopt a more agile and flexible approach to planetary protection, others fear the effective result will be to discount legitimate precautionary measures in favor of achieving major milestones such as a robotic sample return and landing humans on Mars.

Special Treatment

Consider what may become the PPIRB’s most controversial recommendation: NASA, the report says, should consider establishing “astrobiology zones” on Mars—“regions considered to be of high scientific priority for identifying extinct or extant life”—as well as a separate class of “human exploration zones”—places on Mars where the large “amounts of biological contamination inevitably associated with human exploration” would be acceptable.

Presently, a somewhat different set of “zoning regulations” guides Martian exploration. Certain parts of the planet are deemed “special regions” and demand corresponding special treatment—such as stricter spacecraft-sterilization methods—for and by any robots or humans who might venture there. Taking such precautions often leads to costly delays and budget overruns, potentially reducing the overall cadence and efficacy of interplanetary exploration.

Broadly speaking, a special region is classified by the United Nations–affiliated Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) as any locale where terrestrial microbes might readily propagate or where indigenous life might conceivably be found. As liquid water is the cornerstone of all known life, all special regions on Mars are places where liquid water is thought to at least occasionally exist.

How, exactly, future missions using the PPIRB’s newly proposed astrobiology and human exploration zones would work vis-à-vis COSPAR’s special regions is not yet clear. Perhaps to sidestep that issue, the PPIRB’s report recommends that NASA should revisit the categorization of areas that are explicitly not considered to be special regions, and Stern says that despite any differences between the two frameworks, “they are similar in intent.” In the end, he says, the PPIRB’s recommendations for a more agile and nuanced approach to planetary protection “will get more science done and advance our understanding of the solar system and the evolution of life in it more rapidly.”

Law of the Land

This is all more than mere academic debate, because COSPAR’s special regions are a matter of international law, per the U.N.’s Outer Space Treaty of 1967 (OST). Treaties such as the U.S.-ratified OST are considered “the supreme law of the land,” according to Article VI of the nation’s Constitution, says Christopher Chyba, a professor of astrophysical sciences and international affairs at Princeton University.

Because the OST is a multilateral treaty, multilateral agreement among its adherents on its implementation is necessary—NASA and other space agencies may make suggestions, but ultimately it is COSPAR that determines planetary protection standards, which, in turn, intimately influence the associated added costs to interplanetary missions. “Processes in the U.S. can and do feed up to a U.S. government position to take to COSPAR,” Chyba says. “But the U.S. can’t make these decisions unilaterally, at least not without expecting other nations to object, unless we intend to abrogate [the OST]. Since this is the same treaty that bans weapons of mass destruction in outer space, that would be a profoundly bad idea.”

Chyba is sympathetic to the view that current planetary-protection protocols may be excessively burdensome, but he cautions that most experts in this debate are rife with conflicts of interest, because “no one eager to explore space is happy to see higher costs or a slower pace of exploration.” To guard against entrenched biases, he says, decisions of planetary protection should be based strictly on science, not on programmatic concerns or lobbying from any special interests. And, he adds, “if one intends to make a programmatic decision despite the existing science, that should be acknowledged.”

Not So Special?

Prior to the PPIRB report’s release, a document examining whether and how to soften planetary protection rules was already circulating within NASA. Entitled “Is It Time to Update Our Interpretations of Martian Special Regions?” and presented by Dave Beaty of the Mars Exploration Directorate at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, it was discussed last August during a meeting of the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG). Chartered by NASA’s headquarters, MEPAG provides science input and helps prioritize Mars exploration activities.

Among the observations offered by Beaty was that Mars researchers have to date failed to conclusively confirm the existence of any single special region on that planet’s surface despite a concentrated search since 2006. In other words, such precautionary classifications remain, for now, quite speculative despite their significant effects on mission planning.

Moreover, Beaty added, mounting evidence suggests many of the surface features previously thought to signify special regions, such as dark streaks on seasonally-sunlit slopes potentially caused by flows of briny water, could instead be formed in dry conditions that would be inhospitable for even the hardiest terrestrial microbes.

Furthermore, Beaty noted that human missions to Mars would inevitably exceed the strict biocontamination limits set for special regions. And because of astronauts’ life-support needs, they would, in fact, create temporary, local special regions in and around landing sites. “However,” he wrote, “is there a reason this is unacceptable?”

Carol Stoker, a space scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center, acknowledges that a case can be made against aqueous origins for Mars’s dark-streaked slopes, because the streaks are observed to flow downhill in a manner expected for dry material.

“However, that does not mean that liquid processes play no role in their formation, and the seasonality and repeatability of the flows points to some role played by volatiles,” Stoker says. “A habitable environment needs only thin films of water, not a running stream, to support microbes.”

As for how to proceed with future human missions, Stoker believes that no human landings should be permitted until robotic scouts have thoroughly searched for signs of life at potential landing sites. Although the contamination of Mars with terrestrial microorganisms is at the forefront of most experts’ minds, she says the risk of back contamination cannot yet be dismissed. “It is imperative that a reasonable effort to search for extant life be conducted on Mars prior to sending humans,” Stoker says, “because there is no way to ensure that those humans will not bring potential contamination back with them.”

The Road Ahead

Catharine Conley, who served as NASA’s planetary protection officer from 2006 through 2017, says the debate over how to responsibly explore other worlds boils down to a very basic conflict. “We’ve got engineers who are convinced that they know everything and biologists who still acknowledge that we still don’t know very much. Fundamentally, that is the dispute.”

Starting with the Apollo program, Conley says, NASA has solicited advice on planetary protection from top scientists and space agencies around the world—as well as experts in engineering, public communications, ethics, and law and liaison members from across the regulatory agencies of the U.S. government—recognizing that the consequences of interplanetary contamination could have global effects on Earth and human society. “The purpose of soliciting advice from such a wide range of experts was to ensure that NASA’s limited expertise in biological and social sciences and mission-oriented government role did not lead to poorly informed decisions that were contrary to either scientific or regulatory common sense,” Conley adds.

That said, the PPIRB report makes it clear that spaceflight has evolved with new entrants, both private-sector entities seeking to conduct a broad spectrum of space activities and new nations conducting interplanetary missions, such as China and India. In short, the times are changing.

How fast policies can and should change to reflect this new reality remains to be seen. Present and past planetary-protection protocols emerged only after many years of careful discussion between multiple stakeholders. And now the clock is ticking as multiple efforts, public and private alike, ponder ambitious missions to the surface of Mars in the not-too-distant future.

For now, according to NASA’s Zurbuchen, the PPIRB’s findings and recommendations will be passed along to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the NASA Advisory Council to help the agency formulate its official recommendations for COSPAR.

“This is not the last word, by any means, in this planetary-protection modernization process,” Stern concludes. “This is one step along the road.”