NASA’s Mars Exploration Program is in calamitous straits. Cuts to the program in President Donald Trump’s budget proposal for the 2021 fiscal year (FY) could pull the plug on the space agency’s ensemble of orbiters, as well as its only active Mars rover, Curiosity, which has been prowling the Red Planet since 2012.

If unchanged, the budget numbers would, in this calendar year, shutter an aged but functional communications relay and science orbiter, Mars Odyssey, which has operated at the planet since 2001. They would also curtail Curiosity just as it reaches new heights in its ongoing science investigations on Mount Sharp in Gale Crater. The funding shortfall would close out the rover’s work late next year, before it can explore a major transition in the ancient climate of Mars that is thought to be recorded in rocks higher on the mountain.

Furthermore, the FY 2021 budget reduces the science sleuthing of NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) by 20 percent. It cuts the number of targeted observations MRO can execute in half, purging most of the special data products associated with them. Like Mars Odyssey, MRO is a dual-purpose orbiter, serving as a crucial data relay while also providing high-resolution imagery of potential future landing sites.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The diminished budget would also impact the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) spacecraft, scaling back that mission’s science operations to minimal levels. Orbiting Mars since 2014, MAVEN allows researchers to track the ongoing deterioration of the planet’s atmosphere—a process that, billions of years ago, transformed Mars from a warm, wet world to its current cold, arid state.

Interplanetary Pain

More than 100 Mars-focused scientists discussed this grim outlook throughout a mid-April meeting of the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG), chartered by NASA to assist in planning the scientific scouting of that far-off world. All the attendees of the meeting took part remotely, of course, because of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic—another potential source of pain, financial and otherwise, for the planning and operation of spacecraft on Mars, as well as for the federal government at large. With Washington, D.C., now spending trillions of dollars to shore up the U.S. economy, the impact on funding for NASA and other federal agencies remains uncertain but could be significant.

Jim Watzin, director of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program, told the MEPAG gathering that COVID-19 “has had an impact on the program and what we do.” He estimated that about three quarters or more of those directly working on the Mars program has transitioned to a virtual workplace and that it was “still too early to accurately forecast the impacts.”

Scientists planning future explorations of the Red Planet face yet another predicament, too—although one that has little to do with Mars or pandemics. Work is now underway on crafting the Planetary Science and Astrobiology Decadal Survey 2023–2032, the latest of a once-every-10-years effort, led by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, that sets research priorities (and notional missions to fulfill them) for at least the next decade. Spurred by a flood of science findings from the outer solar system, many researchers are now looking past Mars to other destinations—chiefly ocean-bearing icy moons such as Jupiter’s Europa and Saturn’s Titan and Enceladus. After a decades-long glut of Mars-focused missions, the community’s hunger to explore elsewhere is becoming voracious. Could this new Decadal Survey mark the moment when planetary scientists turn away from Mars?

.jpg?w=900)

Artist’s rendition of a rocket lifting off from Mars and carrying material bound for Earth as part of NASA’s long-planned Mars Sample Return mission. Credit: NASA and JPL-Caltech

A Balancing Act

Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, explains that each year the program must balance goals and objectives within constraints on the available budget. “Last year required many difficult decisions: invest in the future, continue what we’ve been doing or find some balance in between. All strong organizations do this. Mars exploration is no different,” she says.

The belt-tightening results of that balancing act have been bittersweet, Glaze says. “We share the community’s disappointments, as well as look optimistically toward our new missions, knowing we did our best within the constraints we had,” she adds. “That being said, we will continue to look for opportunities to minimize or offset the reductions as we move forward. Each year we revisit the budget and its constraints and work to improve the posture and potential of the program.”

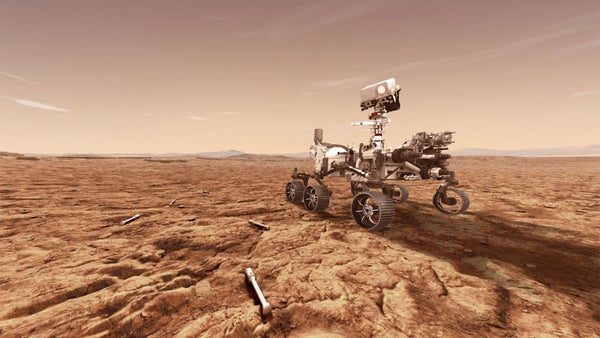

NASA’s next Mars mission—the Perseverance rover—is now being readied for a liftoff this July or August. Meant to be the linchpin for an ambitious international plan to haul samples of Martian material back to Earth, the rover is targeted for a 2021 landing in Jezero Crater, a locale where the ancient environment is thought to have been favorable for microbial life. There the wheeled robot will collect and cache samples of astrobiological interest, which will await retrieval by an as yet unbuilt future mission.

The process of building and launching Perseverance has an estimated price tag of roughly $2.4 billion, Glaze says. That is some $300 million more than the mission’s original estimate. And an additional $300 million or so will likely be required to operate the rover on Mars during its prime mission, which comprises one Martian year (about 687 Earth days).

Shortsighted Punishment

The proposed cuts to NASA’s Mars plans originated in the White House’s Office of Management and Budget. And they are meant to punish the space agency for Perseverance’s cost overruns, says John Logsdon, a space history and policy expert at George Washington University.

“It would be really shortsighted if that penalty undercut the growing momentum toward finally moving forward on a Mars Sample Return effort,” Logsdon says. Getting Mars samples back to Earth for analysis, he observes, has been a holy grail for generations of planetary scientists and was a top priority of previous Decadal Surveys.

“There has to be a better way of enforcing cost control on NASA’s science efforts without jeopardizing their reason for existence,” Logsdon says. “As the country deals with the costs of the pandemic, we need to preserve some of our high-priority future research efforts. Mars exploration should be among them.”

The Mars Exploration Program’s budget is not quite big enough to support a multibillion-dollar sample-return effort while also operating Mars Odyssey, MRO, MAVEN and Curiosity to their full potential, says Richard Zurek, chief Mars scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and an MRO project member.

If it was approved by Congress as is, the president’s FY 2021 budget would have major impacts on every U.S. asset now at Mars, Zurek points out. The value of the data these missions continue to return is enormous, he says, and the cost of replacing all that infrastructure at the planet would be huge. In particular, Zurek says, the Curiosity rover merits sustained support, because its nuclear power source could allow it to continue its explorations for many years to come. Once a mission is ended on another world, any resurrection is difficult, if not impossible. And near-term replacements of those shuttered capabilities appear unlikely.

“There is still so much to do at Mars,” Zurek says. “This is a dynamic planet whose surface and atmosphere change on many timescales: hours to decades.” If the U.S. pares back its operations there, he says, “we will not know what we have lost for a very long time.”

Uncertainty Ahead

“I am worried that the budget threat is real,” says Philip Christensen, a Mars Odyssey team member at Arizona State University. He is principal investigator of the spacecraft’s Thermal Emission Imaging System. Much of that threat, Christensen says, comes from the still unknown extent of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on NASA and its projects. “I would argue that, given the uncertainty of the next few years, NASA would do well to maintain the working assets they have at Mars and keep them active until the next missions arrive,” he adds.

A key enabler of NASA’s ongoing success at the Red Planet is the agency’s continuous orbital imaging presence there since 1997. That lofty perspective allows weather monitoring, remote studies of the conditions surrounding ongoing surface missions and better assessments for the viability of future landing sites.

“If Odyssey [was] turned off, and something happened to MRO, then that continuous U.S. orbital imaging record and presence would be lost,” Christensen says. There are European Space Agency orbiters that collect images, he adds, but NASA does not control them. Furthermore, Christensen notes, the United Arab Emirates, India and China are all planningto launch Mars orbiter missions in the near future. “They are working extremely hard to just get to Mars and go into orbit,” Christensen says. “It seems a bit arrogant to think that the U.S. is so good at getting to Mars that we can turn off a perfectly good, working spacecraft when other countries are doing everything they can just to get there.”

Were NASA to switch off Mars Odyssey, it could lose more than just imagery. “I am very concerned about the possible loss of Odyssey as a relay asset for my mission,” says W. Bruce Banerdt, principal investigator of NASA’s InSight Mars lander, which has been studying the planet’s seismic activity since touching down there in late 2018. “There are other avenues for communicating with InSight, and we would still be able to operate and perform our science if Odyssey were to go away. But we have not yet found any scenario without Odyssey that does not significantly affect our science.”

There may be reason for optimism in spite of the ongoing pandemic and foreboding budgetary forecasts, however. “A large fraction of the country is out of work, and people are sick and dying, so it’s hard for the country to focus on other activities right now,” says Bruce Jakosky, a planetary scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder and principal investigator of the MAVEN mission. “That said, the science and exploration activities within NASA have been seen as having high value for decades, and I don’t see that changing. They were worth doing before the pandemic, and I expect them to be worth doing after the pandemic, too.”