NASA’s pioneering OSIRIS-REx probe has bagged up its precious asteroid sample for return to Earth.

OSIRIS-REx has finished stowing the bits of the carbon-rich asteroid Bennu that it snagged last Tuesday (Oct. 20), successfully locking the material into the spacecraft’s return capsule, mission team members announced Thursday (Oct. 29).

And the sample appears to be substantial—far heftier than the 2.1 ounces (60 grams) the mission had set as a target, team members said. Indeed, OSIRIS-REx collected so much material on Oct. 20 that its sampling head couldn’t close properly; the head’s sealing mylar flap was wedged open in places by protruding Bennu pebbles.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The OSIRIS-REx team noticed that issue last week when examining photos of the head and its collected sample; flakes of escaped asteroid material drifted through the frames. To minimize the amount lost, the team decided to expedite the precise and complex stowing procedure, which was supposed to happen next week.

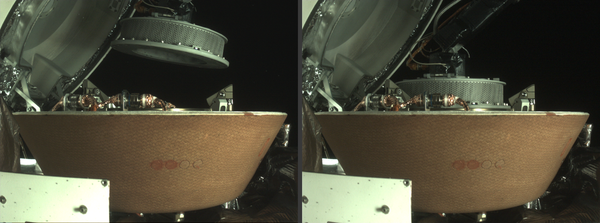

So, over the course of 36 hours on Tuesday and Wednesday (Oct. 27 and Oct. 28), engineers directed OSIRIS-REx to deposit the sampling head, which sat at the end of the probe’s robotic arm, into the return capsule; tug on the head to make sure it was secured properly; sever connections with the robotic arm; and lock up the return capsule via the locking of two latches.

This was all done while OSIRIS-REx was about 205 million miles (330 million kilometers) from Earth, meaning it took 18.5 minutes for each command to reach OSIRIS-REx, and another 18.5 minutes for each update from the probe to come back down to Earth.

“We wanted to only attempt stow one time, and we wanted to make sure we were successful,” OSIRIS-REx mission operations manager Sandra Freund, of Lockheed Martin Space in Littleton, Colorado, said during a NASA news conference Thursday. “And we definitely were.”

The change of plans required a last-minute reallocation of time on NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN), the system of radio telescopes that the agency uses to communicate with its far-flung probes. Because the stow operation was so important and so involved, OSIRIS-REx needed a large block of continuous DSN time, which other NASA missions sacrificed for the greater good.

It’s unclear exactly how much asteroid material now sits in OSIRIS-REx’s return capsule, which will come down to Earth in September 2023. The team canceled a planned post-sampling weighing procedure that would have involved spinning the probe, because this maneuver would have resulted in more sample loss. (Moving the arm—to photograph the sample and conduct the stow operation, for example—imparted grain-liberating acceleration, mission team members explained. So they wanted to minimize such motions.)

But there’s definitely a lot of asteroid material on board, said mission principal investigator Dante Lauretta of the University of Arizona.

The sampling operation on Oct. 20 went extremely well, Lauretta said, and the head penetrated deep into Bennu’s surface—perhaps 19 inches (48 centimeters) or more. The team is confident that OSIRIS-REx pretty much filled its sampling head that day, meaning it likely backed away from Bennu with about 4.4 lbs. (2 kilograms) of collected material.

The losses over the ensuing days appear minimal by comparison—probably “tens of grams” in total, Lauretta said. And recent photos of the sampling head showed that it was still packed. Mission team members could only see 17% of the head’s volume in those photos, but they estimate that about 14.1 ounces (400 g) of Bennu material is jammed into that space, Lauretta said.

If that estimate is accurate, and if the 17% slice is representative of the entire sampling head, then OSIRIS-REx may have held onto more than 4.4 lbs. (2 kg) of sample. Lauretta’s overall prediction is more measured than that, but it’s still decidedly bullish.

“I believe we still have hundreds of grams of material in the sample collector head—probably over a kilogram, easily,” Lauretta said during today’s news conference.

That would be great news. Such a large amount would allow lots of research groups to study the Bennu dirt and rock, and to perform a wide variety of experiments with the pristine cosmic sample. As an example, Lauretta pointed to organic chemistry—specifically, analyses involving sugars.

Sugars are “expected to be present in very low abundances [on asteroids like Bennu], requiring several grams of sample to extract them from,” Lauretta said. “And we thought that would not be feasible with the 15-gram allocation but something that does open up with the larger mass available for analysis.”

(The OSIRIS-REx science team gets to analyze up to 25% of the returned sample. If the total sample ended up being the targeted 60 grams, the team would get to study up to 15 grams of it.)

If all goes according to plan, such experiments will reveal a great deal about the solar system’s early days and the role that asteroids like Bennu may have played in helping life get going on Earth, by delivering lots of water and carbon-containing organic chemicals. Shedding light on such big questions is the chief goal of the $800 million OSIRIS-REx mission, which launched in September 2016 and arrived at Bennu in December 2018.

The mission’s next big steps involve gearing up for the return trip (though engineers are also trying to figure out if they can somehow get a rough mass estimate of the now-stowed sample). Orbital dynamics dictate that OSIRIS-REx must start heading for home between early March and May, and the current plan is to target the earliest part of that window, team members said today.

OSIRIS-REx is NASA’s first asteroid-sampling mission, but it’s not the first one in history. Japan’s Hayabusa mission delivered small bits of the stony asteroid Itokawa to Earth in 2010, and that probe’s successor, Hayabusa2, is scheduled to return a sample of the carbon-rich asteroid Ryugu this coming December.

Copyright 2020 Space.com, a Future company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.