It all began late one night in June 2004, with a small dot swimming into view through the optics of the Kitt Peak National Observatory in the mountains of Arizona. Astronomer Fabrizio Bernardi and two of his colleagues flagged the dot as a possible newly discovered asteroid and confirmed its space-rock status in short order. Initially designated 2004 MN4, the asteroid was intriguing but unremarkable—an object with a width of a few hundred meters (now estimated at 340 meters) about 170 million kilometers from Earth. “It was not particularly interesting at that point,” says Bernardi, now at the Italian space software company SpaceDyS.

Six months later, however, a preliminary appraisal of the object’s orbit would shock the world. Analysis at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California suggested the asteroid had a one-in-37, or 2.7 percent, chance of hitting Earth in 2029. This was the highest probability ever found for a sizable asteroid strike in recorded history, and the object was big enough that its impact could devastate entire regions. “It was the most dangerous asteroid discovered so far,” Bernardi recalls. “People were scared.” The asteroid would come to be called Apophis, after the Egyptian god of destruction.

To the world’s relief, further refinements of the orbit of Apophis ruled out the chances of it impacting Earth for the next century. Yet the asteroid will still get extremely close to us in 2029, when it will pass just 32,000 kilometers from our planet, swooping below the orbits of geostationary satellites. “It’s an exceptional encounter,” says Davide Farnocchia of JPL’s Center for Near Earth Object Studies. Objects of this size only come this close to Earth once “every few thousand years.” Apophis will be as bright as a satellite as it passes through our skies on April 13, 2029, visible to billions of naked-eye observers across parts of Europe, Africa, Australia and South America—and watched closely before and after its encounter by astronomers around the world. Asked how many stargazers will be watching this remarkable encounter, JPL’s Marina Brozovic has a simple reply: “Everybody.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

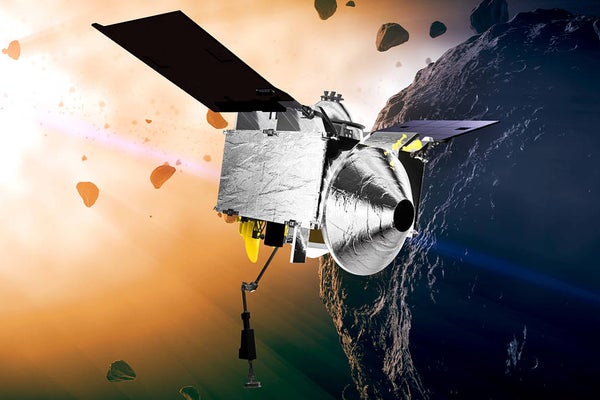

Apophis’s close approach could offer more than celestial eye candy. Scientists have eagerly proposed possible missions to rendezvous with the object on or around its passage in 2029. Now at least one visitor from our planet has been confirmed: NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft, initially launched in 2016 on a mission to collect samples from another asteroid, Bennu, and bring them back to Earth. OSIRIS-REx is currently on its way home from its successful encounter with Bennu, and it is scheduled to drop off its invaluable samples in September 2023. The spacecraft will continue flying through space, however, leading NASA to approve a $200-million extension to the mission. OSIRIS-REx will now rendezvous with Apophis, becoming OSIRIS-APEX (OSIRIS–Apophis Explorer) in the process. “It’s really exciting,” says Daniella DellaGiustina of the University of Arizona, who will lead OSIRIS-APEX’s investigations. “This will be a phenomenal step forward” in our understanding of Apophis.

OSIRIS-APEX will sidle up to Apophis a couple of months after the asteroid’s close encounter with Earth, performing initial reconnaissance before entering orbit around the object in August 2029. Mapping the surface, mission scientists will look for any interesting changes elicited by Apophis’s brief plunge through our planet’s gravitational grip. “The tidal forces could cause small landslides and expose some fresh material,” says Mike Nolan of the University of Arizona, who is science team lead of OSIRIS-REx. “It could be reshaped.”

Surface mapping is only one of the spacecraft’s tasks for its 1.5-year sojourn near the asteroid; pinning down the object’s orbital motion to meter-scale precision is another important goal. This will allow researchers to work out very exact values for Apophis’s future trajectory—and thus its future threat to Earth. “Right now we can predict all the way to 2116,” Farnocchia says. OSIRIS-APEX’s measurements will greatly extend such forecasts, but exactly how far into the future is not yet clear. Some of the uncertainty is because of the “Yarkovsky effect,” a phenomenon in which uneven heating from sunlight can alter an asteroid’s trajectory through space. The spacecraft will measure this effect on Apophis, as well as any changes in the asteroid’s orbital velocity and rotation arising from its 2029 Earth encounter. In each case, Nolan says, the spacecraft’s measurements will allow scientists “to see whether or not our ideas are correct” for how asteroids respond to external forces—critical information for planning possible interventions against Apophis and other potentially threatening space rocks.

OSIRIS-APEX may not be the only mission to visit Apophis, and it is not the only mission with planetary defense in mind. A South Korean team has also proposed a journey to the asteroid, with a spacecraft launching in 2027 and arriving in January 2029, before Apophis’s Earth flyby, to better observe structural changes. And missions with smaller spacecraft, such as Apophis Pathfinder, have been put forward as well. Perhaps even some private astronauts, on a SpaceX vehicle or otherwise, might consider flying up to the asteroid to lay human eyes on it, Brozovic says. “I would not be surprised to have a flyby with a crew of astronauts,” she says. “You could have someone going on a space safari.” Meanwhile NASA is investigating how to deflect an asteroid with its upcoming DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) mission later this year, while China hopes to perform a similar feat around 2025 with a recently announced asteroid-deflection mission. “China is looking to develop its own capabilities in this area,” says Andrew Jones, a space journalist who closely follows the Chinese space program.

At the end of OSIRIS-APEX’s primary extended mission, currently set for October 2030, the spacecraft will approach Apophis and fire its thrusters at the surface from a few meters away. The idea is to kick up material and take a look at the subsurface, revealing more about the asteroid’s composition and structure. The spacecraft also has an extendable arm used to collect samples from Bennu, but mission planners say they currently have no plans to operate the arm at Apophis. If NASA welcomes a further extended mission beyond the initial 18 months at Apophis, DellaGiustina says, using the arm or even landing OSIRIS-APEX on the surface to act as a tracking beacon could become a viable “endgame” objective. Conceivably, she adds, if the spacecraft remains healthy, it could even move on to yet another asteroid.

For now, Apophis poses no immediate threat to Earth. But in 2029, for a brief moment, it will fire a warning shot as it breezes through our skies—followed closely by at least one inquisitive observer. Learning as much as we can about this object now rather than later, when the situation could be far more urgent, may be the best hope for avoiding some far-future catastrophe. “Apophis is the archetype of the kind of asteroid that we’re worried about,” Nolan says. With OSIRIS-APEX’s help, we might just be ready for the next one.