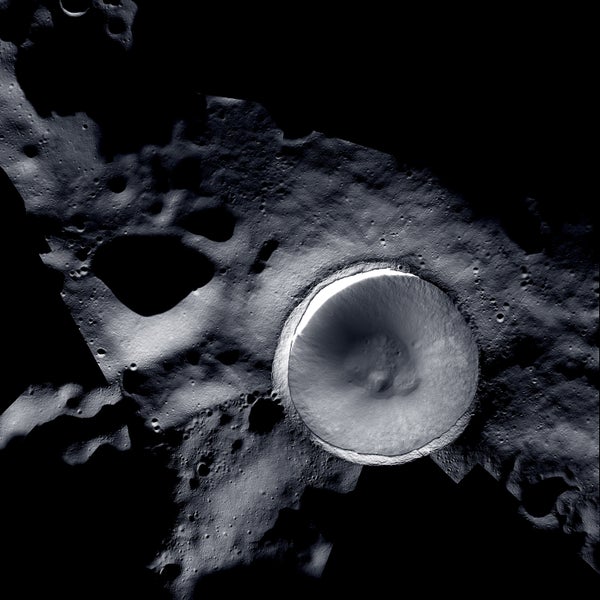

Shackleton Crater pops from the moon’s South Pole, as if a round cookie cutter were just punched into the rocks, in a gorgeous new image that shows portions of the lunar surface that are permanently shrouded by shadow.

The crater gapes at about 13 miles wide and 2.6 miles deep. Its interior and walls are permanently shadowed—they never receive direct sunlight—because of the moon’s slight 1.5-degree tilt on its axis. (For comparison, Earth is tilted at about 23.5 degrees.) That makes it difficult to peer into the crater, which is suspected to hold ice deposits. Some peaks along its rim, which glisten white in the newly snapped image, receive sunlight for much of the year.

To create an image with a crystal clear view of the crater bottom, NASA researchers combined data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera (LROC), an imaging system on the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been orbiting the moon since 2009, and ShadowCam, a NASA instrument onboard Danuri, a Korean spacecraft that launched in 2022.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

These two instruments are complementary. LROC captures high-resolution images on the sunlit areas of the moon’s surface but can’t produce great imagery in low light. ShadowCam is designed to use reflected, rather than direct, sunlight to produce detailed pictures of permanently shadowed spots, but it delivers washed-out photographs of any area lit by direct sunlight.

Combining the two yields mosaics, such as the new one of the Shackleton Crater. In this image, the visuals of the crater floor and walls rely on data from ShadowCam, while the rim and areas outside the crater come courtesy of LROC.

Since its launch, ShadowCam has also provided peeks into other lunar craters and revealed otherwise-invisible features, such as an apparent landslide within Spudis Crater. The lunar South Pole is intriguing, according to NASA, because conditions are so cold and dark in these regions that they might host water ice or other frozen volatiles beneath the surface. Observations taken by an orbiting spacecraft in the 1990s suggested a high level of hydrogen in the subsurface of some of the lunar South Pole’s craters, a possible sign of water ice. A peak near Shackleton Crater is among the proposed landing sites for the Artemis III mission, a NASA effort to send human crews to the lunar surface. If astronauts can extract oxygen and hydrogen from frozen ice deposits within the lunar surface, they may be able to use those resources for fuel and life support, which would enable longer stays on the moon in the future.