Shortly after launching on 1 July, the European space observatory Euclid started performing tiny, unexpected pirouettes. The problem revealed itself during initial tests of the telescope’s automated pointing system. If left unfixed, it could have severely affected Euclid’s science mission and led to gaps in its map of the Universe.

Now the European Space Agency (ESA) says that it has resolved the issue by updating some of the telescope’s software. The problem occurred when the on-board pointing system mistook cosmic noise for faint stars in dark patches of sky, and directed the spacecraft to reorient itself while capturing a shot.

Giuseppe Racca, Euclid project manager at ESA in Noordwijk, the Netherlands, says that the updated pointing system will operate slightly slower than planned. As a result, the main mission, due to last six years, could take up to six months longer. Its scientific goals should not be affected, ESA says.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Mapping the Universe

Euclid is designed to carry out a deep survey of the Universe by mapping the positions of 1.5 billion galaxies in 3D, looking beyond the stars in the Milky Way. But to do so, it will often have to photograph some of the darkest patches of the sky, which have only very faint stars. Euclid must use the known positions of those stars — as previously mapped by another ESA mission, Gaia — to find the correct patch and continuously adjust its position to extremely high precision for more than 10 minutes at a time.

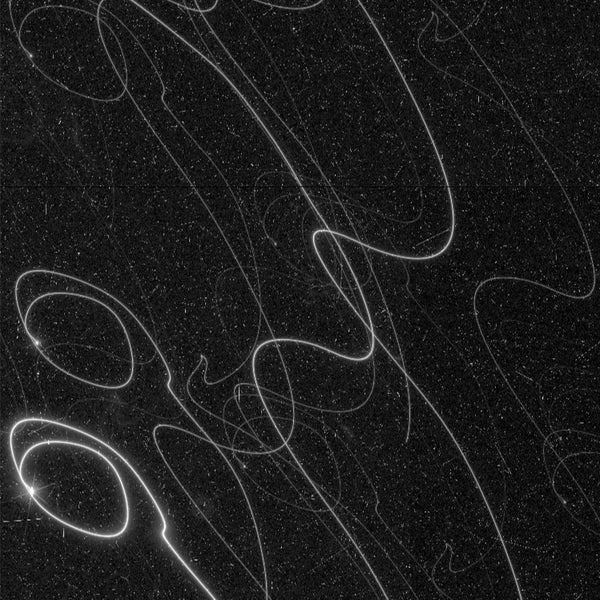

Initial tests of this system showed that, in some cases, the telescope was not pointing stably. Instead, it would wobble, producing test images in which some stars appeared to follow tiny looping trails.

ESA says that the Euclid team, together with its principal industrial contractor, Thales Alenia Space, was able to diagnose the problem quickly. The pointing system uses auxiliary sensors inside the telescope to take periodic 2-second exposures of the field of view. It then matches the stars it sees with those in the Gaia catalogue, to make sure they are in the expected positions. But the sensors also pick up noise from energetic particles such as cosmic rays, which continuously rain onto the probe from all directions, explains Giovanni Bosco, a physicist at Thales Alenia Space in Turin, Italy. Within 100 milliseconds, the on-board software has to filter that noise and single out the real stars.

This didn’t always work out as planned, says Racca. “Sometimes it had too few stars, and it was getting confused. It was losing the guiding stars and then automatically started to look for them again.”

Bosco worked with the team at subcontractor Leonardo in Florence, Italy, to fix the problem by improving how the algorithms filter out cosmic noise. ESA has now tested the system and announced on 5 October that it is working as planned.

Rogue light

Another issue spotted in early imaging tests was that tiny amounts of stray light seemed to be entering the telescope — despite it being protected by a sunshield and wrapped in multiple layers of insulation. The problem was probably caused by a thruster that sticks out to one side of the spacecraft, where it is not protected by the sunshield, says Racca. When the telescope was oriented at certain angles, sunlight was ricocheting off a 1-square-centimetre area on the thruster — the only part of it that is not painted black — and bouncing from the back of the sunshield onto the side of the telescope. A small fraction of this light could be detected by Euclid’s super-sensitive cameras. The mission team found that the problem went away after simply adjusting the orientation of the probe by 2.5 degrees.

Racca says that the mission can now resume its planned commissioning stages, and expects that it will be able to begin its scientific work some time in November.

“When I heard about the problems and the solutions they were trying out, to me it sounded like this will work out,” says Anthony Brown, an astronomer at Leiden University in the Netherlands and a senior member of the Gaia science team. Still, he adds, whenever problems with a space mission can be overcome, “it’s always an immense relief.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on October 6, 2023.