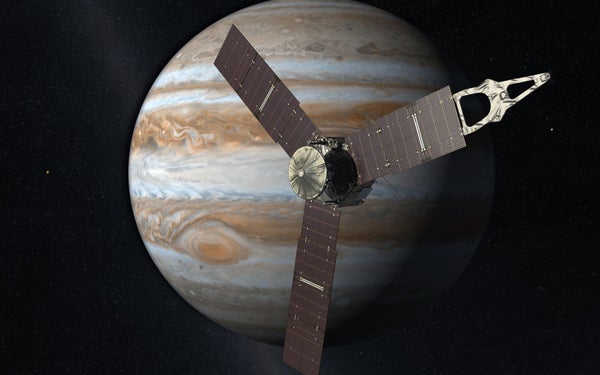

PASADENA, Calif.—NASA's Juno spacecraft has successfully entered orbit around Jupiter. At 8:53 P.M. Pacific time, ground controllers received a telemetry tone of 2,327 hertz—equivalent to the highest D note on a piano keyboard—indicating that Juno’s 35-minute engine burn had slowed the spacecraft enough to slip into the giant planet’s gravitational embrace. Launched in 2011 on a nearly five-year interplanetary voyage, Juno is only the second spacecraft to ever orbit Jupiter, after the Galileo mission that explored the giant planet from 1995 to 2003. During its capture into orbit Juno passed just 4,490 kilometers above the Jovian cloud tops, so close that the planet filled half its sky. Even so, Jupiter is so immense that an astronaut riding along would have seen only about 5 percent of the planet’s cloud-shrouded face.

At 9:50 P.M., the maneuver was officially complete as the spacecraft turned its solar arrays back toward the sun. “I won’t exhale until we’re sun-pointed again,” Juno’s principal investigator Scott Bolton had said at a press conference earlier in the day.

The spacecraft plummeted in from interplanetary space over Jupiter's north pole at about 7:30 P.M., falling ever faster as it plunged deeper into the planet’s gravitational field. Just two days ago its speed relative to Jupiter was nine kilometers per second; midday yesterday, 12 kilometers per second; and by the rocket burn, 54 kilometers per second. The burn reduced its speed by just 1 percent, but that was enough. (Theoretically, the spacecraft was captured by the planet at 8:38 P.M., about halfway through the burn, but confirmation did not come until later.) After skimming so close to Jupiter’s upper atmosphere, the spacecraft soared back up from the planet’s cloud tops at about 9:30 P.M. into a looping, elongated orbit out to 8.1 million kilometers.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Were it not for Juno’s engine burn, Jupiter’s gravitational field would have spat the spacecraft back into the depths of interplanetary space at nearly the same speed as its approach. Far from attempting to reassure the public that such an eventuality would never come to pass, scientists and engineers spent the day warning journalists about it. “Juno is going into the scariest part of the scariest place,” Heidi Becker of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who leads the radiation-monitoring team, said during a press conference earlier Monday. The gauntlet Juno ran at Jupiter held many chances for catastrophe: The spacecraft might have been knocked out by intense magnetic fields (at that distance, 20 times stronger than Earth’s), ionizing radiation (a total dose of 265 rads—more than enough to kill a human being), dust particles from Jupiter’s rings (from which the main engine was completely unshielded) or loss of power if the solar arrays were unable to reorient to the sun.

Now, before Juno can resume high-speed communications via its main antenna, controllers must perfect its alignment with Earth and dampen any wobbling motion, first by firing thrusters, then by warping the solar panels slightly to fine-tune the spacecraft’s orientation. After putting all the scientific instruments into precautionary hibernation last week, the mission controllers are preparing to power them back up on Wednesday. Even then, though, scientists do not expect any decent images or dramatic findings until August 27, when the spacecraft rounds its first orbit and swoops close to the planet again. (Officially, an orbit starts when the spacecraft reaches its farthest distance, or “apojove,” which it does for the first time on July 27. So the next closest approach will be considered halfway through the first orbit.)

The next nail-biting moment will come on October 19, when the main engine is scheduled to fire for a final time, placing the spacecraft into a 14-day mapping orbit. If that goes well, scientists can at last stop fretting about specific milestones and instead lose sleep over Juno’s escalating radiation dose. Initially the dose is minimized by the spacecraft’s polar orbit, which ducks under the radiation belt, but the orbit shifts over time due to the torquing from Jupiter’s gravitational field. As its orbit shifts, Juno will approach the planet at a steepening angle, passing through more intense regions of radiation and increasing its exposure tenfold. Despite being shielded in a titanium vault, the spacecraft’s instruments will be gradually cooked. For now Juno has escaped ending with a bang, but it cannot avoid going out with a whimper.