The virus that causes COVID-19 is a prolific sack of genes that targets not just humans but nonhuman animals as well. And just as humans and animals can infect one another, animals can also infect other animals, says Amélie Desvars-Larrive, an epidemiologist at the University of Veterinary Medicine in Vienna. Scientists have learned a lot about how COVID spreads in humans but less about how it spreads between animals.

To make it easier to study the connections among humans, animals and the virus, Desvars-Larrive and a team of researchers gathered scattered reports of COVID-infected mammals from all over the world to create a public database. Understanding how the virus spreads between nonhuman mammals, and then between those mammals and humans, can help us better manage the current pandemic—and prepare for the next one.

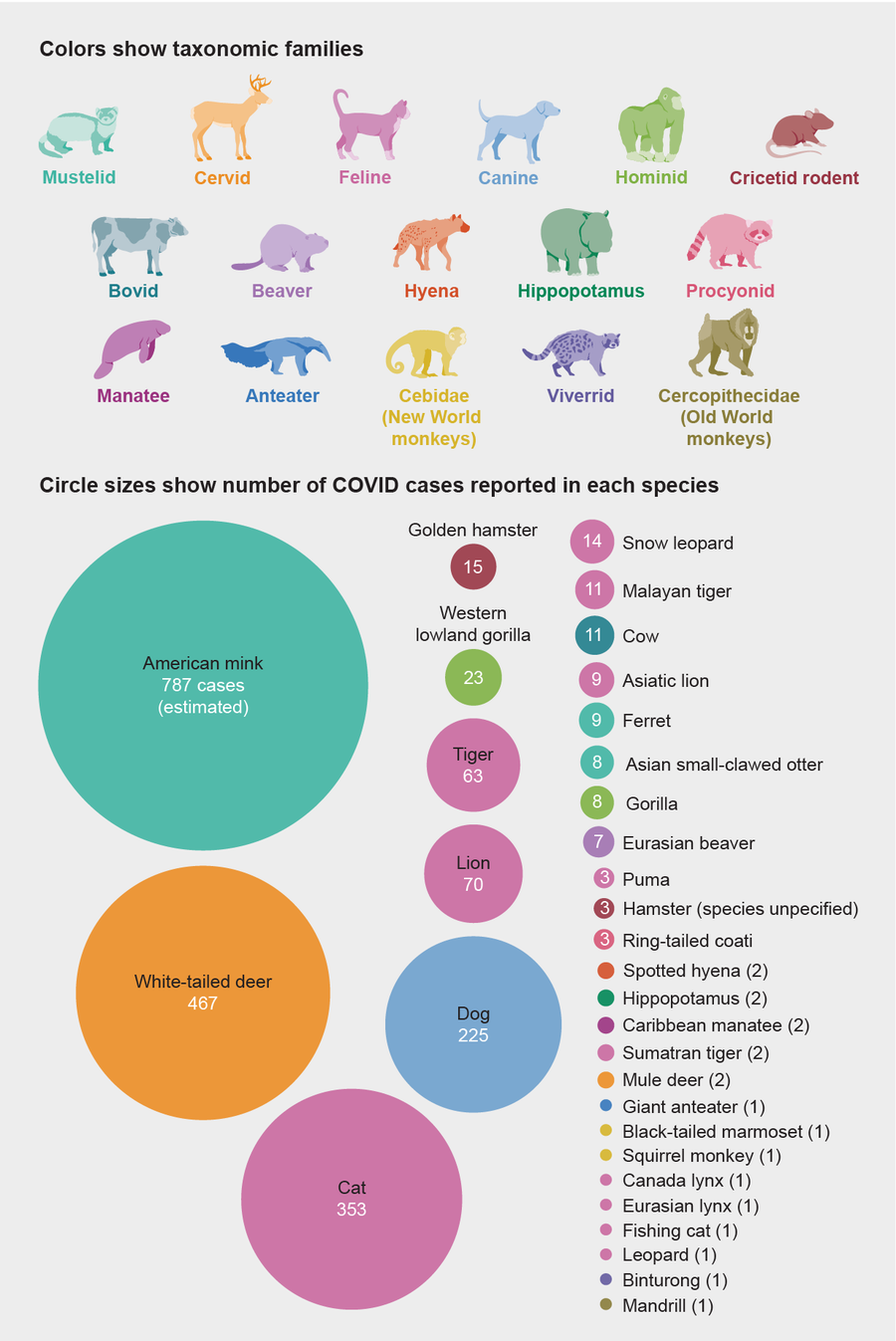

Credit: Brown Bird Design (animals) and Amanda Montañez (data visualization); Source: SARS-ANI Database (as of September 6, 2022), University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, and Complexity Science Hub Vienna

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“We can’t continue to focus on humans, to have an anthropocentric point of view on this pandemic,” Desvars-Larrive says.

COVID has proved highly contagious among many mammal species: Infections have run rampant among captive mink, and fur farmers have had to kill their entire stocks to stop it. Deer appear particularly susceptible to the virus. Many cat species, both big and small, seem to get it as well. Barbara Han, a disease ecologist at the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Millbrook, N.Y., who was not involved in the database project, says having this kind of information in one place—rather than split among multiple sources managed by different organizations and government agencies—will likely make it faster and easier for her team to predict how the virus behaves.

The database is growing as more animals are tested and reports shared, and scientists hope it will help them to track animal-to-animal COVID infections as well as transmission between animals and humans. Han says that beyond just tallying individual infected species, the database will make it easier for scientists to study how the COVID-causing SARS-CoV-2 virus affects mammal communities and entire ecosystems.

“People are fascinated that this pathogen is now in [so many] animals and what it might mean for us,” Han says. “If we don’t have good information about which animals have it now, we can’t get those answers.”