Great Lakes Fish Are Moving North with Climate Change. But Can They Adapt Fast Enough?

The first fish came to the Great Lakes after glacial retreat created them thousands of years ago. Now those fish are on the move again.

Great Lakes Fish Are Moving North with Climate Change. But Can They Adapt Fast Enough?

The first fish came to the Great Lakes after glacial retreat created them thousands of years ago. Now those fish are on the move again.

These Salamanders Steal Genes and Can Have up to Five Extra Sets of Chromosomes

Unisexual salamanders in the genus Ambystoma appear to be the only creatures in the world that reproduce the way they do. Researchers know how, but the why is still being figured out.

An Archeological Dig in Michigan Turns Up Some Surprising Artifacts

Archeologists have found a small mountain of artifacts buried in a farm field that show the presence of some of the first peoples to inhabit the Americas.

Researchers Are Making Nightmarish ‘Coffee’ with Invasive Sea Lampreys

Why on earth would you try to “brew” anything using parasitic fish that slurp the blood and guts out of other fish?

Detroit Has a Large Population of Ring-Necked Pheasants, and They Are Striking

The Motor City is perhaps the only large city in the country with groups of the beautiful nonnative fowl running around its fields and lots.

AI Helps Small City Pull Toxic Lead Water Service Lines from the Ground Faster

Benton Harbor, Mich., needs to exhume thousands of corroded lines, and a machine learning algorithm is helping to figure out where to dig first.

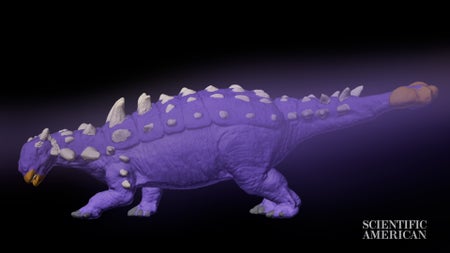

These Dinosaurs Had a Complicated Air Conditioner in Their Skull

Cooling 5,000-pound, armor-plated giants was no small feat.

At the Bottom of Lake Huron, an Ancient Mystery Materializes

The air was likely frigid as the hunter lit a small fire. The caribou would come in the morning—forced through the narrow strip of marshland where he camped. There was nowhere else to go. The land was flanked by water on both sides, and large stones had been laid out in slanting lines to funnel the animals into this bottleneck. The hunter struck his weapon to sharpen its edge in anticipation. In that moment, two glassy flakes splintered away from the point of impact and fell to his feet. They would be buried there for nearly 10,000 years.

In 2013 those two shards of obsidian, a natural volcanic glass, would be recovered from a sample of earth, roughly the volume of a quart of milk, that was pulled from the bottom of Lake Huron, under 100 feet of water. And the story the flakes would tell was one of an even longer journey.

John M. O’Shea of the University of Michigan and his team of underwater archaeologists have found something extraordinary about these two pieces of obsidian: they traveled nearly 2,500 miles from central Oregon before coming to rest at what is now the bottom of one of the Great Lakes.

The samples were recovered from the Alpena-Amberley Ridge, a geologic formation below Lake Huron that connects Michigan to Ontario. O’Shea and his team have been diving at the site for more than a decade, collecting artifacts and environmental samples to prove that 9,000 years ago—as ice age glaciers were receding and the Great Lakes were forming—the area was dry land inhabited by Native Americans, who built hunting structures on it to trap and kill caribou.

Obsidian was highly prized by ancient stone toolmakers. The flakes identified by Brendan Nash, a member of O’Shea’s team at the University of Michigan, have strike marks and sharp, feathered edges—both telltale signs of human modification. This evidence, combined with the distance to the obsidian’s original source, paint a picture of an extensive trade or exchange network that spanned the continent nearly 3,000 years after the end of the last ice age.

Stone tools recovered from the Alpena-Amberley Ridge are much smaller than artifacts found nearby that date to the same time period. This suggests that a group of ancient people, with a different way of life and system of hunting, existed on the ridge around 9,000 years ago.

In their study, O’Shea, Nash and their colleagues wrote, “These specimens provide greater resolution, as well as greater complexity, to an important and poorly understood time period in the North American past.”

In two small flakes, one can gain a view of a world lost to time and the waves.