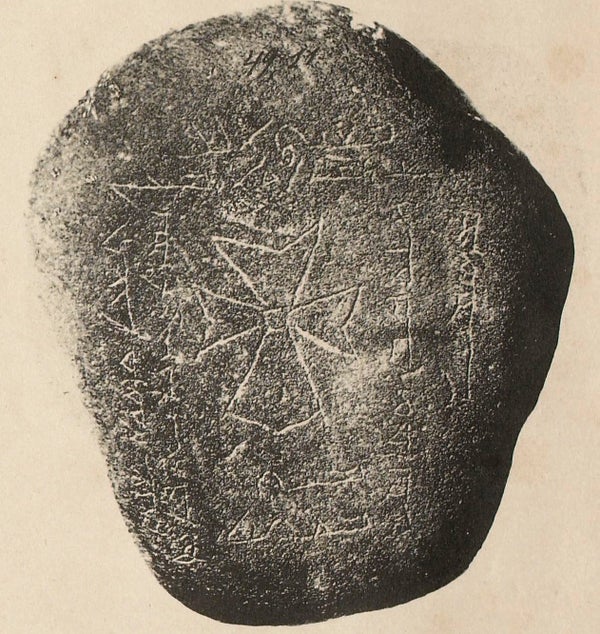

In 1338 or 1339 “Bačaq, a faithful woman” in her 40s who stood just four feet, eight inches, died and was buried in the Kara-Djigach cemetery, about seven miles outside Bishkek, the capital of what is now Kyrgyzstan. Her tombstone was inscribed in Syriac, an Aramaic dialect. She was one of 114 people buried there during those two years—who accounted for one quarter of all the cemetery’s burials while it was in operation from 1245 to 1345. Bačaq’s tombstone does not mention a cause of death, but other 1338–1339 tombstones do: mawtānā, or pestilence. Today it is called plague.

Bačaq’s teeth, as well as those of another woman buried nearby, have now yielded genomic evidence of what researchers suggest is the ancestral strain of the Yersiniapestis bacterium responsible for the 14th-century Black Death pandemic, according to a study published on Wednesday in Nature. The paper also points to this region as the source of that notorious plague, which killed at least an estimated 30 to 60 percent of Europe’s population in a handful of years.

Various regions in Asia have been proposed as the origin of this second plague pandemic—the first being the sixth-century Justinian plague, which historian Procopius claimed killed 10,000 people a day in Constantinople and weakened the Eastern Roman Empire. But virtually all of the genetic and historical data on the second plague has so far come from Europe, says paleontologist and study co-author Maria Spyrou of Germany’s University of Tübingen. “It gave us a very sort of Eurocentric focus on what really happened,” she says. The remains examined in the new study are “the only archaeological evidence that we know of that is present outside of western Eurasia or outside of Europe.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The study analyzed the teeth of five women and two men whom archaeologist Nikolay Pantusov exhumed in the late 19th century from the cemetery in Kara-Djigach and another in the village of Burana, about 35 miles east. Their skulls had been stored in the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

The researchers extracted Y. pestis DNA from tissues inside two of the women’s teeth and sequenced the genomes of those pathogens, which were found to be identical. The teeth of a woman who died in her 50s also revealed Y. pestis DNA, but it was too degraded for a high-quality genomic reconstruction, and no plague DNA was recovered from the teeth of the other individuals.

Next, the scientists compared the recovered Y. pestis strain with 203 modern and 47 historical genomes of the species. The strain they found appears to be the ancestor of Y. pestis strains that evolved around this time in a so-called diversification event, which has long been thought to be linked to the beginning of the second pandemic. These strains have been recorded from the remains of plague victims in Europe, and they are found across the world even today in generally less virulent forms.

Because the newly recovered strain resembles modern ones found in animals in the region, Spyrou and her colleagues suggest it originated in the nearby Tian Shan mountain region on the border of Kyrgyzstan and China, when the bacterium jumped from rodent hosts—likely marmots—to humans.

“I do think the authors show that the strain they reconstruct and analyze is convincingly ancestral” to Western European strains that date from later during the Black Death, says Hendrik Poinar, a biologist who studies ancient DNA at McMaster University in Ontario. (Poinar was not involved in the new study but has sequenced a Y. pestis genome from a Black Death cemetery in London in a collaboration that included two of its co-authors.) He notes that Y. pestis strains are “notoriously clonal,” or nearly identical, and slow to evolve. “So the question now is: How wide geographically was that sequence represented in 1338 and before?” Poinar says. If it was widespread before and up to 1338, he says, it might not be the only basal strain of the second pandemic circulating—and thus could obscure the pandemic’s true origins.

The study’s team also sequenced the genomes of the seven people and found they were most similar to present-day Eurasian populations. But that does not mean they were homogenous. The variety of coins, silk, golden brocade cloths, pearls, shells, precious stones and metals of often distant origin found in some graves speak to the people’s ethnic and geographical diversity—and sometimes their wealth. So do the inscriptions on their tombstones, which give their origins as China, Mongolia and Armenia, among other places.

Such diversity underscores the trade connections in the region, which at the time was controlled by the Mongols. Balasagun, then the closest settlement to the Burana cemetery, was “a center of economic, political and cultural life in Central Asia,” says study co-author Philip Slavin, an associate professor of environmental history at the University of Stirling in Scotland. He translated the Syriac tomb inscriptions into English and contextualized the site based on Pantusov’s diaries.

The cemeteries’ location along the Silk Road bolsters the idea that intercontinental trade played a role in the dissemination of the plague during the Black Death. It also raises the question of why the disease did not sweep eastward across Asia, however.

One of the next steps for the researchers is to try to reconstruct the bacterium’s 1,800-mile trip from Central Asia to Europe based on genetic archaeological and historical data—but first they have to find those data. Revisiting old collections, as the team did in Kyrgyzstan, may provide some potential lines of inquiry. “I do wonder whether there are additional similar collections that we might have an opportunity to study in the future,” Spyrou says. “I really hope so.”