Afghanistan and Pakistan — the two countries in which polio is still endemic — are closer than they have ever been to eradicating wild poliovirus, the World Health Organization (WHO) said last month. It’s a surprising turn given that the eradication effort had been criticized as floundering as recently as last year. With a small number of cases and limited geographical spread of the virus, scientists agree that the two nations stand a real chance of stopping transmission of wild poliovirus this year, but only if the eradication programmes in these countries can overcome persistent social and political challenges.

“This is the best epidemiological opportunity these two countries have had concurrently,” to stop wild poliovirus from circulating, says Hamid Jafari, director of polio eradication at the WHO. With sustained, targeted and coordinated vaccination efforts, “there’s now a shared opportunity” for them both to succeed, he adds.

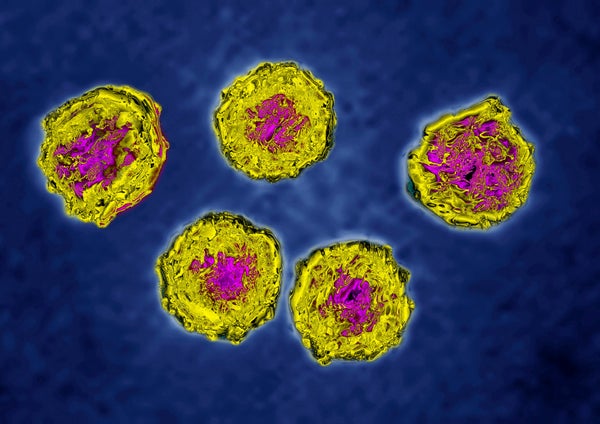

Wiping out wild poliovirus, of which there are three strains, termed serotypes 1, 2 and 3, has been the goal of global eradication efforts since they began in 1988. Types 2 and 3 were successfully eradicated in 2015 and 2019, respectively, but type 1 continues to circulate in Afghanistan and Pakistan 12 years after India quashed all forms of the wild virus, and 7 years after Africa did the same.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

An analysis of polio transmission dynamics, published in 2020, found that global polio eradication efforts were “not on track to succeed” in their goal of eliminating wild poliovirus type 1 by 2023. Fears that eradication was falling out of reach increased again in 2021, when wild poliovirus broke containment lines and emerged in eastern Africa. One case in Malawi in 2021 and eight cases in Mozambique in 2022 were found to be genetically linked with a 2019 Pakistan strain, which had been circulating undetected in Africa for two years. As recently as February 2023, an article in the New England Journal of Medicine suggested eradication of the virus had been “unsuccessful”.

However, case numbers are down in 2023: Pakistan has reported just two wild polio cases so far this year; Afghanistan, five. In 2022, they recorded 22 cases combined. Poliovirus also seems to be cornered: transmission is now restricted to seven districts in Pakistan’s Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, and two provinces across the border in eastern Afghanistan — Nangarhar and Kunar.

The reduction is thanks to how the countries have rebounded from the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic, political upheaval in Afghanistan in 2021 and widespread flooding in Pakistan in 2022, with vaccination campaigns of renewed intensity and expanded environmental surveillance for signs of the virus.

In October 2022, the WHO’s Technical Advisory Group on polio eradication recommended changes to the campaign with the aim of concentrating resources in the highest-priority areas while allowing nationwide immunization to continue.

Jafari says that this major shift in vaccination strategy was a crucial move that helped Afghanistan and Pakistan to edge even closer to eradication, along with rapid responses to outbreaks.

The countries need to be free from wild poliovirus for a three-year period, during which no new cases are diagnosed and no poliovirus is detected in environmental samples, before the wild type 1 virus can be declared eradicated from the region — and the world.

“We’ve never seen what we’re seeing now,” says Natalia Molodecky, an independent epidemiologist and modeller, who has worked closely with the WHO and with Pakistan’s polio programme. “The fact that we’re in this situation in August, the high-transmission season, is promising.”

Not only are the recent cases of polio in Afghanistan and Pakistan contained geographically, but the genetic diversity of the virus is at an all-time low. Mutations accumulate when a virus circulates freely, and new strains diverge. But only one genetic cluster of wild poliovirus type 1 is currently present in each country — down from 11 in Pakistan and 8 in Afghanistan in 2020. This suggests the virus isn’t circulating much.

‘All in’

Both Pakistan and Afghanistan are on high alert for traces of silent polio infections. Molodecky says for every child paralysed with wild poliovirus type 1, there are about 200 asymptomatic infections. “So, when you see a case, it’s only the tip of the iceberg,” she says. Infected people who have not been vaccinated can spread the virus.

To increase surveillance, Pakistan has markedly increased its number of sewage testing sites in the past 18 months, and Afghanistan has expanded its network by one-third. “So they’re looking harder and harder, and finding less and less of the virus,” says Jafari.

Kimberley Thompson, director of Kid Risk, a non-profit organization based in Orlando, Florida, that models vaccine-preventable childhood diseases including polio, says that both countries need to stay on the front foot, and not dial back vaccination campaigns too soon. That has happened in the past, when health authorities were overly confident that they had stamped out polio. “This is the time to go all in,” Thompson says, on the basis of her team’s modelling of eradication efforts in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Attaullah Ahmadi, a public-health researcher at Kabul University of Medical Sciences in Afghanistan, agrees that the epidemiological evidence suggests Afghanistan and Pakistan are “on the brink of eradicating the wild poliovirus”. However, both countries have been close before, and have fallen short, and Ahmadi says that many obstacles persist.

Deadly militant attacks still occur in both countries. Parental refusal and false beliefs regarding vaccines, fuelled by misinformation and poor health literacy, are also barriers to vaccination, Ahmadi says.

To improve vaccine acceptance, health officials must continue working with community leaders in tribal areas, he says. Female health workers are another crucial part of vaccination campaigns, Jafari notes, because they help to build a rapport with mothers and caregivers. “Failing to sustain these efforts could lead to a resurgence in cases, jeopardizing the progress made so far,” Ahmadi cautions.

Since August 2021, vaccinators in Afghanistan have been able to reach up to 4.5 million children in previously inaccessible areas, with the backing of the Taliban. But political uncertainty looms in Pakistan: the parliament dissolved this month amid political and economic crises, with elections to be held later this year.

Vaccine-derived polio

Wild poliovirus finally seems to be cornered, but vaccine-derived polioviruses threaten to undermine global polio eradication efforts as a whole.

Oral poliovirus vaccines (OPVs) contain weakened polioviruses that can sometimes revert to virulent forms, spread among unimmunized individuals and cause paralysis. Since January 2020, vaccine-derived polioviruses have sprung up in more than 50 countries — including some that eradicated polio long ago.

Injectable, inactivated poliovirus vaccines are not known to cause or seed paralysis cases, but they do not contain polio outbreaks as effectively as OPVs. Vaccination programmes must use oral drops with careful planning to ensure that outbreaks are stopped without seeding more. High vaccination coverage is the best protection against vaccine-derived polioviruses.

Molodecky points to an outbreak in Afghanistan and Pakistan that began in July 2019 (and lasted until 2021) as an example of how vaccine-derived poliovirus can be controlled and eliminated with vaccination strategies, informed by modelling. “It’s definitely possible to do, even in complex environments,” she says. No vaccine-derived polioviruses have been detected in either country since the outbreak was contained in 2021.

And that was before the availability of a novel OPV (nOPV), which Jafari says “will set us on a path” to eradicating vaccine-derived poliovirus, too. Nearly 700 million doses of nOPV2, which targets vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2, have been administered across 31 countries since March 2021, and similarly stable formulations are being developed for types 1 and 3.

Eradicating all polioviruses is certainly possible, says Thompson, although it will take a lot of effort. “It requires resources, it requires commitment and it requires us to really work together to figure out how to finish this.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on August 15, 2023.