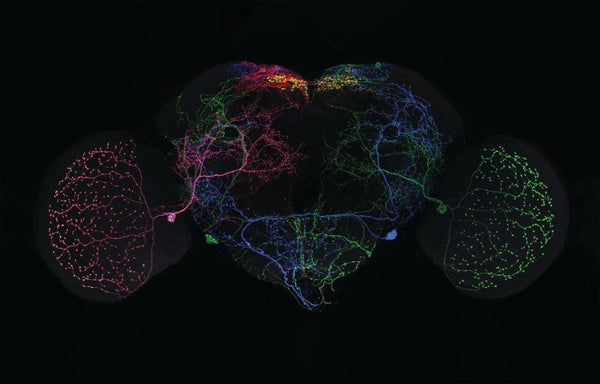

Everybody wants to get inside a fruit fly's head. These insects' simple brains are invaluable to neuroscientists studying information processing and task management, and a new, unprecedentedly detailed map of fruit fly brain connections now makes that easier. After years of work on their FlyLight initiative, researchers at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Janelia Research Campus in Ashburn, Va., have compiled photographs of more than 74,000 fruit fly brains—detailed down to the individual neuron—from flies in over 5,000 genetically modified lineages.* This image shows one such fly brain, with brain lobes and individual activated neurons clearly visible.

The more detailed a brain connection map (called a connectome) is, the better it helps scientists understand how nervous systems work. “The brain is a giant neural circuit,” says Geoffrey Meissner, a Howard Hughes researcher and lead author of the new mapping study in eLife. If you want to know how the brain works, he says, “you have to know the map of the circuit.”

But even in a 200,000-neuron fly brain—compared with a human's 86 billion to 120 billion neurons—it can be difficult to get images of single brain cells and their shapes. Lewis & Clark College biologist Tamily Weissman-Unni, whose work focuses on cataloging brain circuits, notes that a neuron's individual shape holds key information about the kinds of input it receives and the role it plays. Likening this to examining a freeway system, she says, “We know where the big, huge pathways are, but your question might be about what an individual car does on that freeway.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

For decades scientists have mapped neurons by observing fruit flies with inserted genes that produce a yeast protein called Gal4 when neurons carry out certain processes. Gal4 activates another added gene that can produce pigment proteins visible by microscope—letting researchers see what brain parts are involved when the organism does anything from flying to tasting food. Unfortunately, it's hard to discern individual cells when a slew of neurons activate at once.

The FlyLight researchers developed a method they named MultiColor FlpOut, in which various inserted pigment-producing genes interact with an enzyme called Flp to label activated neurons with different colors and levels of pigmentation. Scientists then assembled these samples like a puzzle to map the respective chains of individual cells that activate during certain activities—and to build their impressive new database.

To see more, visit scientificamerican.com/science-in-images

*Editor’s Note (6/26/23): This sentence was edited after posting to correct the description of the FlyLight researchers’ affiliation.