There are limits to our natural resources. At some point they run out, or we ruin them. When either happens, both the physical system and the human system on Earth are hurt. In 2019 the Earth Commission—an international team of scientists that I co-lead—collaborated with the Future Earth scientist network and the Global Commons Alliance to convene a large group of researchers to establish boundaries for resources that could keep the planet and its people safe.

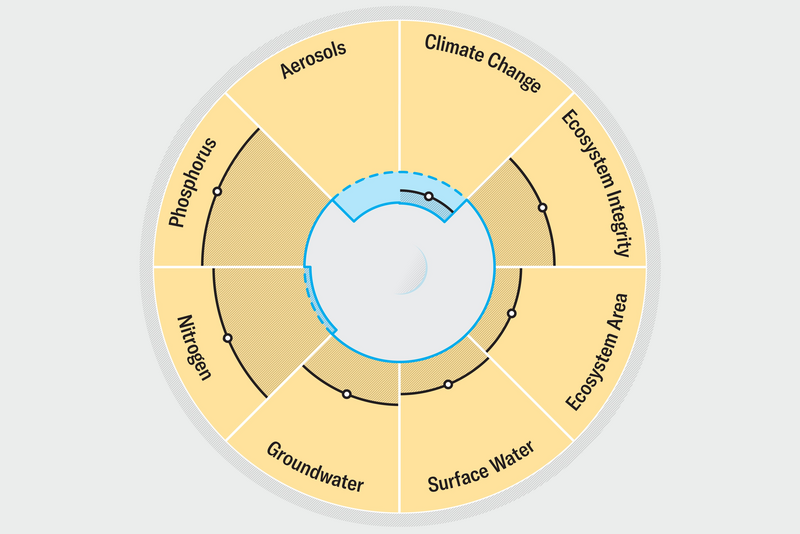

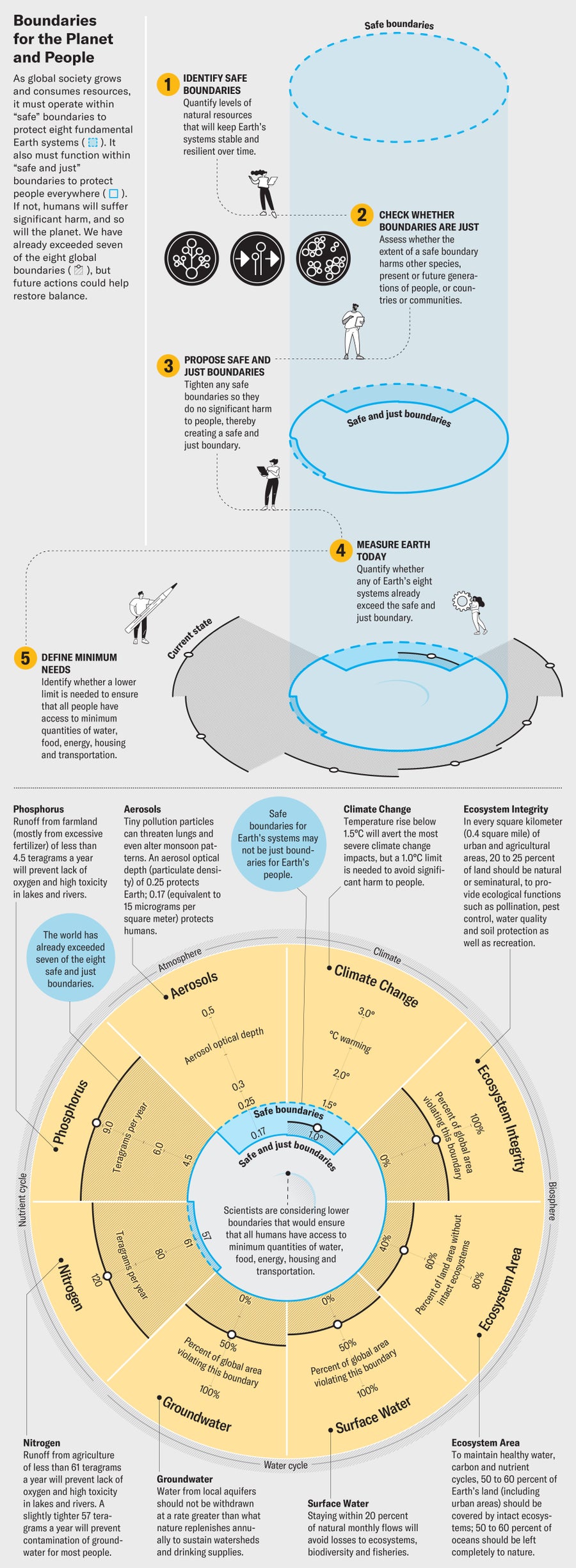

We began with five domains that cover the major components of Earth's interconnected systems: climate, biosphere, water cycle, aerosols and nutrient cycles (nitrogen and phosphorus). In each case, rather than setting a single threshold, we set two: a limit that was “safe” for Earth overall and a “safe and just” limit that would do “no significant harm” to people worldwide. In all cases, the safe and just limit is equivalent to or stricter than the safe limit. Our group is now working on limits for two other domains: oceans and chemical pollution such as microplastics.

The hard part, of course, is determining what is “just” and putting a number on that evaluation. Consider climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns that the world must prevent global warming from surpassing 1.5 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels; beyond that, it is highly likely that we will reach tipping points for significant worsening of damaging climate effects. So 1.5 degrees C is a boundary intended to keep Earth and people relatively safe. Yet even though we have raised global temperature by only 1.2 degrees C thus far, tens of millions of people are already exposed to hot, humid conditions extreme enough to kill them and certainly oppressive enough to prevent them from working to meet their basic needs. Furthermore, millions of people living along the seashore and on islands are being forced to move because coastlines are disintegrating as sea level rises and because coastal storms are getting increasingly severe. That is certainly unjust. In our group's assessment, a temperature increase of 1.0 degree C is the safe and just limit for climate change—it adheres to a fundamental principle of justice, namely, not causing harm to people.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In some cases, we considered local effects when setting the safe and just limit because global patterns can mask serious problems at the local level. Air pollution, for example, can hurt people in a specific region before it harms people worldwide. Aerosols, or fine particulates, less than 2.5 microns in diameter released into the air by a range of industrial processes are beginning to alter monsoon rain patterns on which millions of people depend for growing food. Those patterns are global. Aerosols can also harm human lungs, and although levels are not yet high enough to do so worldwide, local air pollution can be deadly. Such pollution is disproportionately high in poorer regions. Every year seven million people die from air pollution. We set a safe limit for aerosols of 0.25 to 0.50 aerosol optical depth, or AOD, an estimate of the amount of aerosols present in the atmosphere. We also set a safe and just limit of 0.17 AOD, which takes into consideration the problem of local air pollution. This matches World Health Organization standards stating that fine particulate pollution should not exceed 15 micrograms per square meter, which translates to an AOD of 0.17.

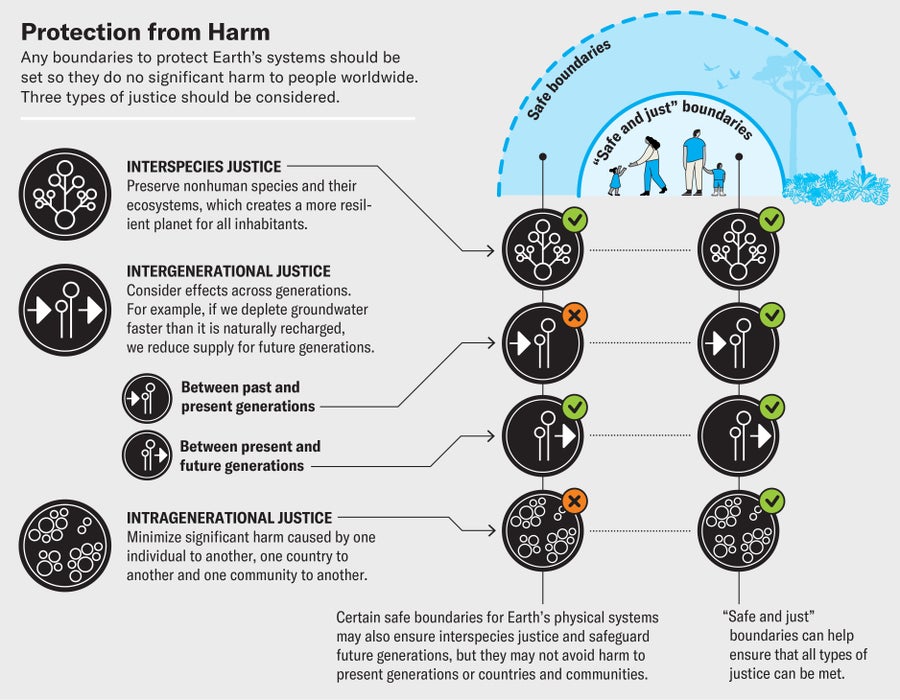

Defining what constitutes significant harm is difficult. Existing environmental problems already harm millions to billions of people. To set our boundaries, we considered tipping points in Earth's systems, relations between humans and other living things (which we call interspecies justice), harm to current and future generations (intergenerational justice), and effects on countries and communities—what might be called intragenerational justice. This kind of thinking led us to set the safe boundary for climate of 1.5 degrees C and the safe and just boundary of 1.0 degree C.

Credit: Angela Morelli and Tom Gabriel Johansen/InfoDesignLab

Our safe and just boundaries for the biosphere are that ecosystems in 50 to 60 percent of the planet's land area should be kept intact, and 20 to 25 percent of managed land in each square kilometer of cities and rural areas should be reserved for nature. Intact ecosystems provide shade (relief from increasing heat) and help local food production; bees and earthworms can travel only short distances, and they are vital to the plants, trees and food we grow. Natural land within cities protects mental health: studies show that our sense of well-being improves when we have trees and plants around us. Ideally, every city, school, hospital and home will reserve a certain percentage of land for nature so that all people—even those living in high-rise buildings or slums—have access to it.

People's development and pollution of landscapes in the past reduced the space available for nature today. If we continue these trends, we will put future generations at risk. It is time for us to manage land for the benefit of nature as well as humans—and we can learn a lot from how Indigenous peoples and local communities have successfully maintained biodiversity on their lands. Targets need to be implemented justly; some countries, especially poorer ones, have large tracts of pristine nature left, but it is unfair to put the burden of protecting such natural resources on them. Richer nations may have to do more.

Similar considerations apply to safe and just water use. For groundwater, we should not extract more than is recharged naturally. This makes sense from an intergenerational justice perspective: if we keep depleting groundwater, there will be less water for the future. Draining groundwater can also cause land to subside and allow salt water to intrude farther inland, ruining agricultural land for farmers today and for food production in the future.

Our latest work indicates that in 2023 the world had already surpassed the safe and just limit for seven of the eight boundaries. Only the aerosols limit has not been breached globally, although local aerosol boundaries have been crossed in many parts of the world. We have also found that in more than 50 percent of all places on Earth, at least two of the safe and just boundaries have been crossed; South Asia, for example, has high air pollution as well as excessive water extraction.

With so many boundaries already crossed, it might be tempting to conclude that there are too many people on Earth, but our results show that the environmental pressure of meeting the needs of the world's poorest people is roughly equal to the environmental pressure created by the richest 4 percent. The problem is excess consumption of resources by the wealthy. To meet the minimum needs of the poorest, we will have to transform the way in which nations and markets allocate and price resources. And that means transforming how we care for our Earth.

The dominant way of handling environmental problems has been to identify their direct causes—for example, if too much fertilizer is put on agricultural land, we might impose standards about how much can be distributed per square kilometer. But this kind of regulation does not address the true root cause, which is the global agricultural system driven by our global economic system. Our idea of safe and just boundaries calls for tackling the underlying causes of environmental degradation and poverty. The better we care for our Earth, the better we care for one another.

Credit: Angela Morelli and Tom Gabriel Johansen/InfoDesignLab

Credit: Angela Morelli and Tom Gabriel Johansen/InfoDesignLab; Source: “Safe and Just Earth System Boundaries,” by Johan Rockström et al., in Nature, Vol. 619; May 2023 (reference)