On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Last winter, you might have seen the headlines about rising hospitalizations from respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV. Healthcare providers now have tools to help prevent lower respiratory tract disease caused by RSV in adults 60 years and older. This fall and winter is the first respiratory season when RSV vaccinations will be available in the United States to help protect against RSV for older adults.

Scientific American Custom Media recently sat down with Dr. Temi Folaranmi, Vice President and Head, US Medical and Clinical Affairs, Vaccines at GSK, in this GSK-sponsored segment to learn more about RSV, the immune system, and vaccinations.

------

Megan Hall: Well, Dr. Folaranmi, it's such a pleasure to talk with you today. Thank you for joining me.

Dr. Temi Folaranmi: Thank you for having me on your podcast.

Hall: So, before we dig into the details of this conversation, I'm really curious about you and your background. Specifically, you've spent your whole career combating diseases and viruses. You've worked on meningitis, polio, HIV, both in Nigeria and in the US. So, what sparked this interest for you?

Folaranmi: I trained as a physician and I also have postgraduate training in public health and public policy. This training is important for my career because I think the intersection between clinical practice, public health and public policy and the broader scientific community is so important, that our public health policy have strong foundation in science. And I've spent a lot of my career has been to inform public health policies and programs based on sound research and data. I think, for me, growing up in a developing country like Nigeria, I see various cases of infectious disease. I developed that passion very quickly, that it’s an area that I want to contribute to focusing on disease prevention, as well as treatment. And I feel that one area that I can really make an impact is in that public health space, where we can use data to make population-level decisions that will have impact on the life of a broader group of people versus the individual patient treatment that I do on a daily basis.

Hall: Tell me a little more about how you went from someone seeing that in your own country to being motivated to do this kind of work.

Folaranmi: I figured that for me to be able to do this kind of work, I need to have the right set of training. So, having completed my medical degree in Nigeria, I came to the US to pursue a Master's Degree in Public Health at Harvard University. And upon completion of that training, it became very apparent to me that people who makes public health policies actually more politicians and not the expert. And so, I figured I needed to have a training that allowed me to speak a language that these people speak. And that led me to take a training in public policy so that I can use my scientific knowledge to inform good conversations with policymakers who make public health decisions.

Hall: That’s your background. The topic of today’s conversation is RSV. For people who don’t know what RSV is, could you just define it for me?

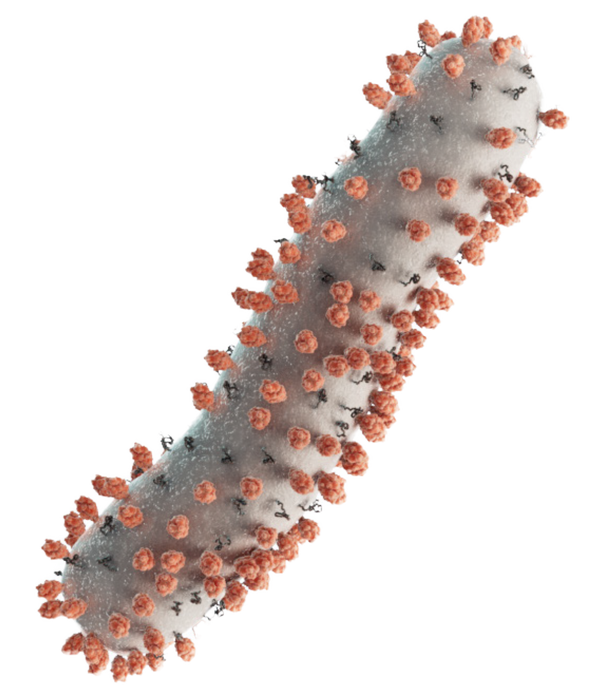

Folaranmi: Absolutely. So, RSV, the full meaning of RSV is the respiratory syncytial virus. It’s a common contagious respiratory virus that usually causes mild symptoms. However, older adult are more likely to have severe outcomes from the virus because the immune system typically weakens as we age. Each year, approximately 177,000 adults aged 65 and older are hospitalized in the US due to RSV. And an estimated 14,000 of these cases result in death. And so, for even adults age 60 and older, some data suggest that they receive an increased risk of severe RSV infection that could lead to hospitalization as well. So, what you see is while RSV may present as mild cold symptoms for certain individuals, it could present severe outcomes for certain individuals.

Hall: What happens to the body as it ages that makes it more vulnerable?

Folaranmi: That’s a good question. So, as we get older, our immune system tends to weaken over time, and that puts us at higher risk of certain diseases. And because it’s difficult for our body to put on defenses against these diseases, it makes us more vulnerable to these infections. And on top of that, if you now have conditions that makes you even more vulnerable, issues such as obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, chronic heart failure, the risk of severe outcome from RSV could be worse. So, what RSV does is that even in elderly individual, it could present as common cold, but in some cases, it could be severe. It could present as cold in certain individuals. It could present as even worse outcomes.

Hall: So, some people make the mistake of thinking, I’m fine, but it’s actually more serious than that if they have underlying conditions.

Folaranmi: Yes. But you know, what’s interesting is that, for the most part, RSV is not even diagnosed because people think it’s a common cold, they just want to be in bed and just wait it through. But in certain situations, it will worsen.

Hall: Can you give me a brief overview of what got us to this point when it comes to preventing RSV?

Folaranmi: So, RSV vaccines have evaded scientists for over 60 years. Scientists have been searching for ways to get ahead of RSV as early as 1955 when a virus was discovered in chimpanzees suffering from respiratory symptoms. Now we know that several factors have made tackling RSV challenging. This include multiple mechanisms that RSV uses to invade the innate immunity. In addition to that, the lack of durable protective immunity induced by natural infection, meaning that even those who have the infection from RSV, they don't get any protection from that. And the last piece is also the decline in the immune system as we age. So, when you compare RSV to other viruses, the virus is particularly smart at evading our immune system because it lives primarily outside of the body, on the surface of our breathing passages. It stayed protected from many of the typical immune responses that we have. But thanks to all these recent advances now we know the scientific community has fresh insight into the protein that helps us develop immunity against RSV. That specific protein is called the surface fusion glycoprotein F. That protein is involved in the initial phases of infection. And so, if we can target that protein, it can help us tailor our approach to how to meet the needs of people who are particularly at risk.

Hall: So, what is your message to people who are 60 and older or to the people who treat them?

Folaranmi: Older adult including those with certain underlying medical conditions need to know their risk factors for RSV and should speak with their healthcare provider if they develop cold-like symptoms, and also discuss their risk for severe RSV illness. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that adults 60 years of age and older speak to their care provider about RSV and vaccination. I recommend that healthcare providers make themselves familiar with this recommendation from the CDC. Healthcare providers and patients should also discuss other appropriate vaccinations during the respiratory illness season. In terms of access, patients with Medicare Part D will pay no out-of-pocket expenses for CDC-recommended vaccines. RSV vaccination may also be covered for commercially insured patients at no cost when administered in-network. So, patients should ask their healthcare provider about coverage for RSV vaccination.

Hall: Great. Well, Dr. Temi Folaranmi, thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me today.

Folaranmi: Thank you for having me on your podcast.

Hall: Dr. Temi Folaranmi is the Vice President and Head of US Medical and Clinical Affairs, Vaccines at GSK. GSK is a global biopharma company with a purpose to unite science, technology and talent to get ahead of disease together.

This podcast was produced by Scientific American Custom Media and made possible through the support of GSK.

Trademarks are owned by or licensed to the GSK group of companies.

Copyright 2023 GSK or licensor.

RSAAUDI230006 December 2023

Produced in USA