The U.S. influenza season has arrived much earlier than usual. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention first detected the early increases of flu activity in mid-October. The agency noted that the phenomenon was happening in most of the country, but more intensely in the Southeast and in south-central regions. A month later, levels of the virus continue to rise steeply. According to the latest CDC flu report, 25 states or jurisdictions now experience high or very high levels of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness, which is characterized by fever plus cough or sore throat.

Infectious disease expert William Schaffner, a professor at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, says the rise came four to six weeks earlier than usual. Each flu season is different, but the season’s early arrival was still unexpected. “It was a very big surprise, even to the experienced influenza watchers, that influenza appeared, rose dramatically and became very widespread so early in the season,” he says.

Tennessee, where Schaffner is based, is one of the jurisdictions with very high levels of respiratory illnesses at the moment. “In our urgent care clinic at our medical center, one third of the people coming in test positive for influenza,” Schaffner says. “That’s enormous, and it indicates a very wide spread.” Schaffner has also observed an unprecedented increase over the past three weeks in the number of patients in his practice who are hospitalized with influenza.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The CDC estimates that so far this season, there have been at least 2.8 million illnesses, 23,000 hospitalizations and 1,300 deaths from flu.

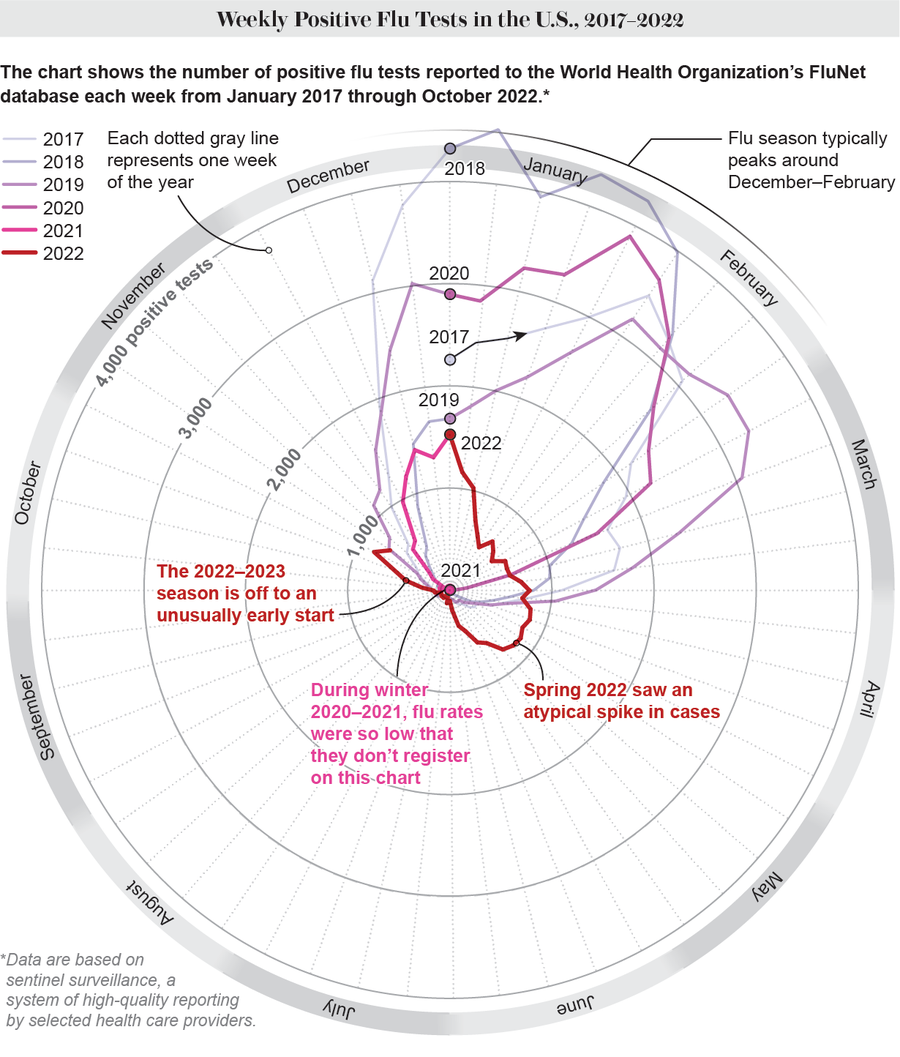

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Source: FluNet/Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System at the World Health Organization (data)

Why Did the Flu Arrive So Early?

The reasons behind the early flu season are not entirely clear, experts say. It is also not possible to predict how severe this flu season will turn out to be.

Flu all but disappeared in the U.S. in 2020 to 2021, which coincided with the COVID pandemic. And this lack of exposure to flu could have affected immunity, according to the CDC. “Reduced population immunity, particularly among young children who may never have had flu exposure or been vaccinated, could bring about a robust return of flu,” the agency stated on its website in October.

“Typically, the population-level immunity is what counts in terms of how many infections we are going to see” in a given season, says Arnold S. Monto, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Michigan School of Public Health. “Now almost everybody is going around unmasked, so we have the situation where [flu] transmission can go back to what we have normally seen,” he says. The fact that fewer people currently have antibodies against the flu because they weren’t exposed to it during the pandemic may be facilitating the spread of the virus, he adds.

That doesn’t mean that lack of exposure to a virus impairs an individual’s immune system, a misconception that is sometimes referred to as “immunity debt.” “Yes, we’ve had less experience with the influenza virus for the last two seasons. But that doesn’t mean our immune system is in any way weakened,” Schaffner says. “We’re still perfectly capable of fighting off the virus and responding to the vaccine.”

What Happened in the Past Two Years?

The low number of flu cases in the past two years is often attributed to the implementation of preventive measures against COVID, such as masking and practicing social distancing.

Although those behaviors may have played an important role, other factors could be involved. According to epidemiologist Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) at the University of Minnesota, the key to understanding why other respiratory viruses all but disappeared in 2020 and 2021 lies in how these viruses interact with each other.

“We’ve learned in the past that when you have a seasonal virus circulating, it may dampen the ability of other viral respiratory pathogens to take off,” Osterholm says. One example of this phenomenon, known as viral interference, goes back to the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, when almost no one was practicing social distancing or masking. Researchers believe that the circulation of a type of common cold virus called human rhinovirus (HRV) in France may have delayed the H1N1 influenza epidemic in that country. Subsequently, H1N1 seems to have delayed the following local wave of the common virus known as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). (RSV is now surging again in the U.S., after a pause during the COVID pandemic’s first year and a large peak in cases in summer 2021.)

While RSV is still increasing nationally, it recently started to decrease in the Southeast and in south-central and north-central parts of the country, according to a recent CDC media briefing. “In those three regions, it seems like RSV is trending downward, and influenza is beginning to increase or surge,” José R. Romero, the director of CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during the briefing. Exactly how these viruses interact with each other on a population level is not yet well understood, but scientists have increasingly been interested in studying this type of interference.

What Can People Do to Protect Themselves?

While it is impossible to predict how big the 2022–2023 flu season will be, Schaffner says it’s safe to assume that there will be plenty of flu transmission during November and into December, since the western and northwestern parts of the U.S. have not yet been affected extensively.

The most important thing people can do to protect themselves from flu is get vaccinated, experts say. The CDC recommends that every person six months and older get the flu vaccine annually. That includes pregnant people. As cases are going up, now is the time to get your shot if you haven’t already. Experts note that the vaccine doesn’t guarantee you won’t get infected. But much like the COVID vaccine, it considerably reduces the risk of serious illness and hospitalization. You can get information on flu and COVID vaccination sites at Vaccines.gov. And it’s safe to get both shots during the same appointment.

The CDC estimates that, as of mid-October, more than 26 percent of adults had received a flu vaccine this fall—slightly higher than the estimated 23 percent at the same time last season. This level of coverage is similar to the most recent flu season before the pandemic, when flu shot coverage was 29 percent in adults by the end of October 2019, according to the CDC.

Additional habits to prevent the flu are avoiding close contact with people who are sick, staying home when you have symptoms, covering your mouth and nose with a tissue when coughing or sneezing, and washing your hands often. People may also consider masking again. “If you’re in a venue where people are in close proximity to each other, it’s never a bad idea to mask,” Monto says. “Masking will prevent transmission not only of COVID, but of the flu.”

Vaccination, however, continues to be the gold standard to prevent severe disease, no matter how big or small the flu season turns out to be. “Predictions about flu are a hazardous business because you’re so frequently wrong,” Schaffner says. “This is not something we should try to predict to determine whether or not [to get] vaccinated. Just get vaccinated every year.”